Jeremy Herbert’s fortress and moat implied stage are reached by the audience filing through a deserted psychiatric waiting room in the underbelly of the Young Vic’s main space. The smell of bleach catches the back of the throat.

On the table, patient Christopher’s file, also the obligatory box of paper tissues, on the floor, bits of chewed up or spewed out Orange, on the pastel walls a white board scrawled upon in red, in our ears shouts and screams and swearing from the rest of the ‘inmates’ we never get to see. The waiting room is both a representation of somewhere real and perhaps also an idea of how the public might imagine such a place to be. Do the screams and bawls in our ears represent how we think mentally unwell people may act or sound? Or are they the sounds of those who are lost in the administrative corridors of the mental health system? What’s the crossover between myth and reality? Director Matthew Xia defines his art form as shaping atmospheres throughout the course of an evening. The atmosphere here is abrasive, hard on the senses and, frightening.

This is alright because Joe Penhall’s play is obsessed with personal perceptions of what sanity is or isn’t (and this can be frightening and alienating) so it fits. So does the idea of the empty moat surrounding a meeting space in which paternalistic and ardent Bruce, a young white doctor, and his mentor, overbearing consultant Robert, clash over whether Christopher, a young black man, can be released into the community at the end of his 28 days sectioning.

The spatial dynamics are as clever as Penhall’s text. Bruce and Robert go back and forth trying to enforce their theories upon the other: Bruce thinks, or wants to think, that Christopher’s illness may mask a more serious case of schizophrenia and he does everything in his power to prove this ideology in practice. Robert, anxious to shore up the evidence for the theories in his groundbreaking book, wishes to believe that Christopher is merely a victim of cultural misunderstanding and that he has suffered no more than a minor psychotic illness compounded by racist attitudes and wants him to go home. Whilst all this is going on, Christopher is sent away and skulks in the little moat in full view as Bruce and Robert dissect his character and pour over the spoils as if dividing land after a colonial take over.

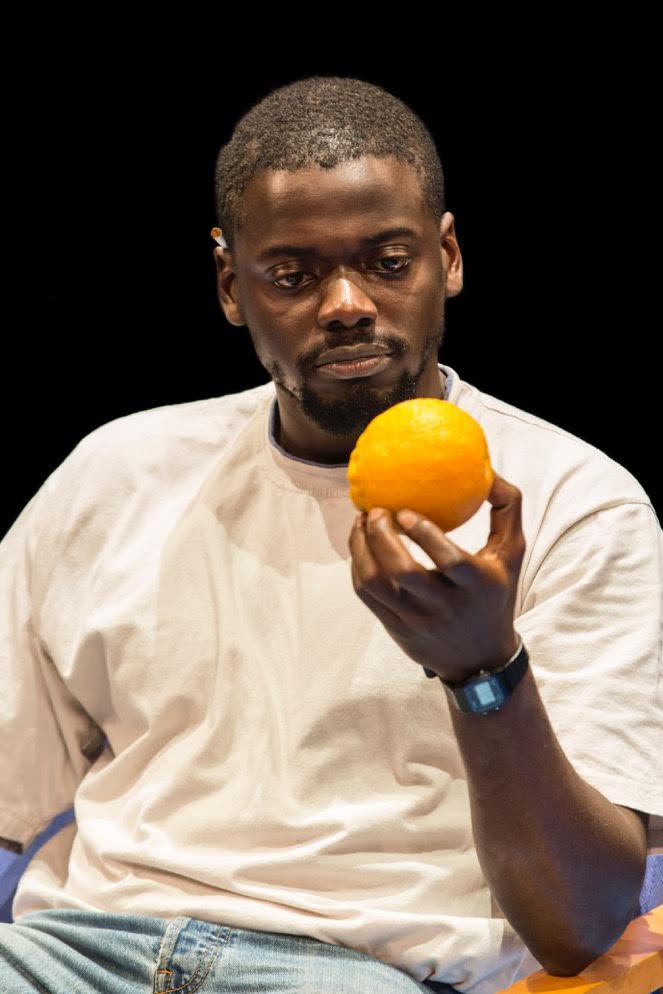

We don’t know how ill Christopher may be. He ducks and dives to avoid the blows from Bruce and Robert, as skilled as they at trying to get what he wants from each by giving each what he thinks they want: is he acting up with Bruce when he insists that Oranges are blue, or is he really psychotic? When he falls in with Robert and insists that he’s Idi Amin’s long-lost son, is this merely because he realises that this is what the consultant wants? Does he deliberately wish to conform to political or cultural stereotypes in order to find some sense of identity and fit in? Or is he pushed? But when Daniel Kaluuya’s Christopher suddenly drops into a chair, shoulders slumped and wails that he does not know who he is any more or what to believe, it’s as though we see through the layers to the real man and what he is becoming: a helpless victim of the doctors’ paralysing arguments, theories and arbitrary choices. Power corrupts is the message.

For most of the time, Penhall makes the audience feel as fractured and as divisive as Christopher must. But sitting in the round on the steeply raked seats, director Matthew Xia sets us up as if jurors in a courtroom; we are unconsciously asked to make up our minds about the patient and to decide whose theory we may plump for. But we can’t, the beauty of Penhall’s text is that we can see both sides of the argument, whilst empathising with the victim. If Christopher really does see Oranges as blue and is not reacting to Bruce’s clever verbal manipulations, then something is wrong (from the perceived norm). But, says Robert, may its OK to see the flesh and skin of Oranges as blue. And, as improbable as it may be, why can’t Christopher be related to Idi Amin? And even if he isn’t, but still believes it and concocts such fantasies and stories to help him get through life, is that reason enough to have him sectioned? Every man lives with his own delusions and illusions after all, it’s only that most aren’t usually revealed to prying, critical eyes. And it’s usually when they are, that man becomes unhappy.

The play successfully highlights a problem endemic within the mental health services: that once you fall into the system, it might be quite hard to get out again. And it is a system that is not about helping you cope with mental health issues, but is more desiring on diagnosing and finding the elusive cure. But it also explores how ethnocentricity and cultural specificity can influence personal opinion. Robert wishes to alienate Christopher from a common culture, by insisting he can only be defined by his own, whilst Bruce is adamant on pulling the other way by mutually recognising him through more persuasive and inclusive dialogues. Everyone fights to be master and not slave.

But the play also exposes the cruelties of blind, oppressive ambition which rocks up where ever there are humans. It’s hard to like any of the characters: at least consistently. David Haig’s Robert exposes a steely coldness behind all that public school bluster and bumbling which masks a hard, calculating trickery: he is a real psychological illusionist who is at least twenty steps ahead of everyone else. He’d make a good chess player. Luke Norris’ Bruce is tortured by the thought that his career may come to an end and can only think of making an impression and safeguarding his future. You’re not going to trust either of them as far as you can throw them, but then, is it ethically right and proper and fair to trust anyone? Meanwhile, Kaluuya’s psychically blocked Christopher (he just needs a girlfriend) dances between them like a puppet on a string.

Unsparingly the production reveals the contradictions and power complexities that accompany our natural desire to help others.

cast includes: David Haig, Daniel Kaluuya, Luke Norris

written by: Joe Penhall

directed by: Matthew Xia

design by: Jeremy Herbert

at the Young Vic until 2nd July 2016