It's obvious that the story of the illegal refugee camp in French Calais near the border with the UK will be remembered as the biggest spontaneous settlement of people in Europe who want not just to receive political refugee status, but who have the aim of getting to the particular country they've always regarded as their pipe dream.

Most Europeans mistakenly think the illegal refugee camp appeared near Calais in spring 2015, when, having crossed whole Europe from Turkey to France, columns of refugees settled here before the main frontier for which they were striving. In actual fact, the first illegal settlements appeared there more than 15 years ago – in 1999. Yet in those times migrants considered Calais as a springboard to get to Britain.

Nine small settlements were established there initially, and the French government tried to show an understanding attitude and provided one of the camps called “Jungle” with money to open a number of bathrooms, toilets and food distribution centres for migrants. The camp, which later gave its name to the settlement, was on the site of a former landfill approximately five kilometres from the town centre.

History and geography

A flow of migrants to Calais can be regarded as a continuous process. There have always been attempts of migrants from different countries to cross the Channel and get to Britain. Calais is like a mirror image of Moroccan Tangier, through which African refugees try to get to Spain. Before the establishment of the EU the flow was rather small due to many borders that refugees had to overcome, but that problem soon disappeared. It was enough to enter Greece, Bulgaria or Romania and then get to Calais. The journey took several days, or two weeks maximum.

In 1999, the Red Cross opened a refugee camp in Calais. It became overcrowded in less than a month. Migrants began to settle nearby in tents and makeshift shelters. The settlements were demolished by the decision of the government in 2002 due to two riots among refugees.

Further developments followed the same pattern: refugees occupied different free sites, the authorities ignored it for some time and bulldozed settlements with the help of police as soon as the number of refugees became critical for Calais. The biggest conflict took place in 2009, when almost 1,000 migrants, mainly from Afghanistan, lived in the camp. The camp was demolished again, and about 300 people were arrested for resistance.

Refugees didn't hurry to settle in Calais after the brutal demolition. Only a few migrants decided to stay here. But even this insignificant inflow was enough for the camp to reach more than 1,000 residents by the beginning of 2014. The trend was increasing, and illegal camps near Calais became a home for more than 3,000 migrants by the beginning of spring of 2015.

Maria Alyokhina (Pussy Riot) in the “Jungle” camp

Graffiti by Banksy at the camp entrance

Spring blitzkrieg 2015

European governments scarcely foresaw how the armed military conflict provoked by Assad's Syrian government could end. The flow of refugees from Syria rushed to the EU, overcoming one border after another. Their route lied through the sites where border services had worked in quite a relaxed mode. Refugees won clashes with border guards and crossed borders despite that fact that they meet brutal force on a number of borders. Having entered EU, refugees faced little resistance.

The situation could have remained under control if the tide of refugees included only Syrians. But the first success of crossing borders worked as a detonator – refugees and economic migrants from about a dozen of countries joined the columns of people fleeing the war. As a result, migrants who wanted to get to Britain settled in the “Jungle”.

It was the time when even Europeans – residents of Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina – joined refugees, hoping to get refugee status and allowance in richer EU countries. Kosovo and Bosnia were the first countries to be named as the states whose citizens are not allowed to obtain refugee status, and the flow of migrants stopped growing.

The “Jungle” camp had sprawled to several hectares by the end of summer 2015, and the number of refugees living there reached 6,000 people and further grew to about 7,000 by the beginning of 2016.

Good Chance Theatre in the “Jungle”

Acting lessons in Good Chance Theatre

Playwrights Joe Robertson and Joe Murphy, founders of Good Chance Theatre

We have a dream

Huge white letters on the slope of Eurotunnel road read 'We Have a Dream.' Perhaps, it is this paraphrase of Martin Luther King's words became the slogan that best reflects desires of “Jungle” camp migrants.

It's hard to understand without visiting the camp why these people, who don't have the right to get refugee status in the UK, but persistently seek it, have gathered in this particular place. You can see plenty of graffiti in the camp that cry about the dream of getting to the UK and migrants' love for their “promised land”.

We failed to fully “decode” migrants' thoughts and find an explanation why they are so obsessed with the idea of getting to Britain.

Of course, one of the rational factor that explains this desire is the language. Many camp residents speak English, some learn it, gratefully accepting language lessons from volunteers. Those who don't know English believe they can learn it fast through immersion. Apart from that, there are probably no other rational factors.

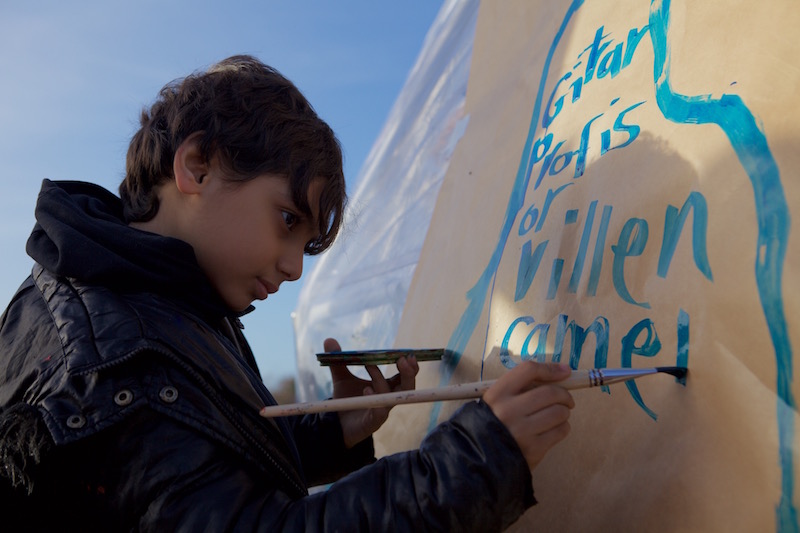

It may seem strange, but here you feel real sincere love for Britain. Even if “Jungle” inhabitants don't speak about it, you cannot get rid of this feeling in the camp. You can see Scottish or Welsh flags in certain places, and their presence in an Iranian cafe is not just an occasion – the owner can clearly explain why he wants to live exactly in Glasgow. Or a kid drawing on a scrap of cardboard can tell you how his family fled a small Syrian town because their house had been bombed, but he knows that there's a town in England where they will be happy again once they get there.

Even if you tell migrants that the UK has curtailed all migrant adaptation social programmes in recent years; that state support will only be enough to buy food; that processing an asylum application may take several years – it is not taken negatively. They say they are ready to wait for as long as it takes.

The first reference that came to your mind after talking to “Jungle” residents is a literary recollection of the first American settlers: the same belief in the land where everyone will be happy; the same migrants' skills of settling in and improving new territories; the same persistence in achieving their aim.

At the end of 2015, the French government decided to install shipping containers converted to contemporary houses and settle migrants there. Houses for 1,500 people are still vacant, because potential residents must be fingerprinted and complete a registration procedure. Migrants believe it will hinder their legalisation in the UK.

It's hardly possible to get the exact number of migrants in the “Jungle”. The only thing you may know for sure is home countries of camp residents who formed compact ethnic groups: Afghanistan, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, Kurdistan, Kuwait, Sudan, Syria. Each ethnic group is represented by a different number of migrants. The largest and most organised group is an Afghan one. The second and third largest groups are Iraqi and Iranian.

The number of camp residents is constantly changing: some cross the border illegally; some leave the camp, anticipating the upcoming demolition; some come to the “Jungle”, having failed to get what they wanted in one of the EU countries. Special services that count refugees estimated their number at from 6,000 to 7,000 people in different periods.

All migrants have come a long and incredibly hard way to find themselves just a few kilometres from their dream, but the dream appeared to be so far for them when they came to it so close.

French zugzwang

Having reached Calais, migrants found themselves in the situation that is called zugzwang in chess. It is a situation when any move will only weaken the player's position.

Today, even if they wanted to help migrants, the French government would find it difficult to do without violating a number of domestic laws and regulations, including the fundamental international document that regulates refugees' rights – the Refugee Convention. Most migrants from the “Jungle” unwittingly violated not one but a number of provisions of the document that was signed and ratified by the absolute majority of countries.

Firstly, most migrants in Calais are not refugees de jure, because they arrived from the countries that don't have military conflicts, so the term “refugee” as defined by the Refugee Convention cannot be applied to them.

Secondly, even being refugees, they didn't apply for asylum in the first democratic country they entered. It means that they were guided not by safety problems but by economic feasibility, which puts them in a position of economic migrants who don't have the right to obtain refugee status on the basis of persecution even if it really took place.

Thirdly, they involuntary poisoned mind of a considerable part of people against them in France and the UK, as well as in most EU countries, which does not encourage governments to look for compromise at all.

Meantime, residents of the “Jungle”, waiting for their future to be determined, have created their own living structure – a settlement with the infrastructure that more and more reminds a real city.

A closed refugee zone in the camp

The Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Church

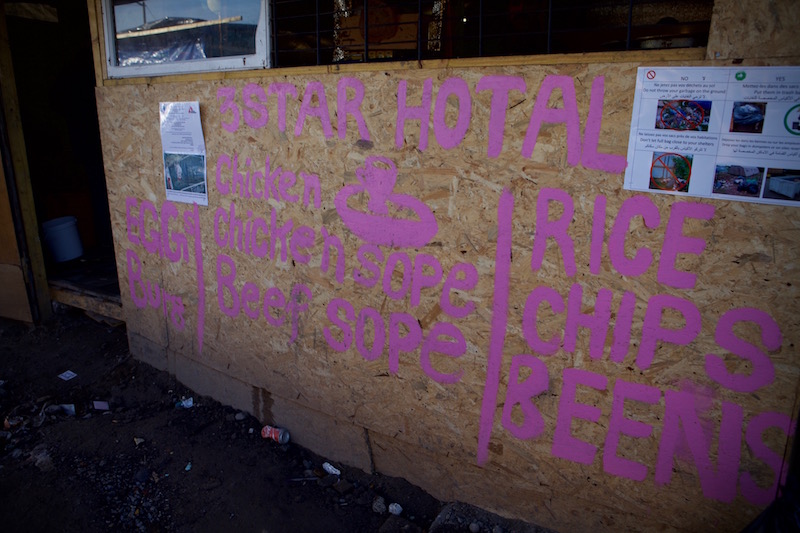

Three star hotel

The “Jungle” started as a tent camp and later grew into something absolutely resembling a city, with its streets, shops, restaurants, barbershops, laundries, hotels and houses, poorer and richer ones.

The very structure of the “Jungle” is a complex of districts divided in accordance with the ethnic principle. The biggest district you meet at the entrance from the side of Calais is the Afghan one. Besides houses, you can see there the best restaurants, barbershops and bathrooms combined with laundries. It may seem unbelievable, but infrastructure is expanding and getting better every day in terms of quality, though the camp lives without external inflows of money.

It's obvious that migrants use the money they took from their countries. Many used to be if not rich, but not needy. There are construction workers, teachers, engineers, bakers, cooks and many service sector employees. They confirm their skills here, in the “Jungle”. A British theatre manager, who came to Calais as a volunteer and visited a barbershop in the Afghan sector, admitted he was surprised at the quality of work at a low price (5 euros for a haircut). In the same way we were surprised at the quality of food in the Afghan restaurant Young Afghan, where a set of roast chicken with rice, hot beans with spinach, lavash and tea cost us 8 euros. The quality can be compared to that of an average London cafe.

The camp population consists of 95% men and only 5% women. Conflicts between male inhabitants spark from time to time, but the police can do little due to the closed camp structure. A dead body of an Iranian man was found in the camp during our first visit to Calais. It wasn't even established if he became a victim of a local conflict inside the Iranian group or an external conflict with Afghan people. The conflict between Iranians and Afghan people has been developing for a year, and a part of Iranian migrants had to leave the camp fearing for their life. Even many locals don't know the nature of the conflict – whether it began right here or was brought here from a long joint journey through countries.

A part of women, also those with their children, lives in a closed secured area of the camp that has been functioning here for several years. They have places to sleep, a medical centre and a food distribution centre. Strangers can't enter this part of the camp, and only a few people from the illegal part of the “Jungle” are allowed there every day to take a shower.

Besides restaurants, barbershops and laundries, a number of public spaces, opened and run by different NGOs, work in the illegal part of the camp: an Ethiopian Orthodox Christian church, a mosque, a medical centre, a library, a vaccination centre, an information centre, Good Chance Theatre, which also functions as cinema, holding four screenings a day and showing films translated into four most popular languages in the camp.

Good Chance Theatre is one of the main centres attracting the most progressive migrants. Created at the initiative of two British playwrights Joe Robertson and Joe Murphy and uniting volunteers of the entire British theatre field, this space organises the most effective events both to educate all residents of the camp and to defend the most vulnerable “Jungle” inhabitants – children without parents.

A humanitarian mission is delivering free blankets

Cultural landing force

Impressive British cultural forces of prominent actors, playwrights and musicians landed in the “Jungle” on February 21 to support three hundred children who live in the camp without parents. Actor Jude Law called on PM David Cameron to take a decision on 300 unaccompanied children and expedite the process of asylum application consideration for 90 children who have family members in the UK. The petition also urged not to demolish the camp at least until the children problem is solved.

Playwright Tom Stoppard, actors Toby Jones, Matt Berry, Shappi Khorsandi, Juliet Stevenson, producer Sonia Friedman, director Stephen Daldry, singer Tom Odell, heads of Belarus Free Theatre – this is not the full list of those who supported the initiative of Jude Law and Help Refugees and came to the “Jungle” to hold an event on the stage of Good Chance Theatre and support the petition to defend minor refugees, which by that moment was signed by 150,000 people.

The campaign of the artistic community was welcomed by refugees, supported by left-wing politicians and widely covered by international media, but the decision on giving refugee status in the UK to 90 children has remained “behind the scenes”. It could have been expected. The acting British government prefers not to make such steps public even if the decision is positive in order not to promote the incident and give grounds for other migrants to repeat such actions.

Playwright Sir Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard, director Stephen Daldry and actress Juliet Stevenson

Actor Jude Law

Theatre producer Sonia Friedman

Actor Toby Jones

Daniella Kaliada

Sabrina Guinness

Singer Tom Odell

Tom Odell and Belarus Free Theatre's managers Clare Robertsonn, Georgie Weedon and Paul Finegan

Jude Law, Belarus Free Theatre's artistic director Natalia Kaliada and Tom Stoppard

A jump to the dream

Most men and teenagers in the “Jungle” go to “jump” almost every day. It means they leave the camp in the morning with the hope not to return there. They find bridges, overpasses and slopes from which they can get to the highway or railway tracks to climb onto trains, cling to lorries or sneak onto ferries to reach Britain. Approximately 7-10 people a week manage to do it, and “jumpers” get a chance to fulfil their dream.

Besides attempts to “jump”, migrants can go to the black market of traffickers who smuggle migrants to the UK. Their services cost from £5,000 to £7,000. Of course, this option is available only for those having such a big sum of money. But even the money doesn't guarantee that a migrant won't be found by border guards, who have been working amid increased security for the last two years.

It's worth noting that British border guards control the French-UK border both at home and in France. They received this right in accordance with the Treaty of Le Touquet signed by then French president Nicolas Sarkozy on February 4, 2003. These measures were supposed to tighten border control and security of the Channel Tunnel and tackle illegal immigration.

Calais Phoenix

The French authorities took a decision on 25 February 2016 to demolish a large part of the “Jungle” refugee camp on the outskirts of Calais. About 2,000 refugees lived in the southern part of the camp due to be demolished.

The decision was not easy – aspects of tackling the European refugee crisis provoke hot debates among politicians. It's hard to forecast today what measures can bring the problem under control without worsening the situation. That's why the process often sinks in discussions without any results.

Seven thousand illegal migrants is a big number that can be compared the population of a small European town. One can hardly analyse how people will behave after the demolition of the camp, the measure that the French authorities are eager to use.

One of the most serious problems related to the camp demolition is that a London court took a decision in January that many identified children who have relatives in the UK can reunite with their families. These children are taken care of in the “Jungle” while their cases are being processed. If the camp is demolished, minors who have the right to reunite with their family will drop out of sight of relevant agencies and melt in another illegal settlement.

Nevertheless, the process of the demolition of the camp has begun, and those who lived in the cleared sector remain without shelter. No one knows what will happen further, but we can say with high probability that the “Jungle” will rise from the ashes like a phoenix, as we can see for the last 15 years in the camp inhabited by people fleeing wars and conflicts.

Europe is divided over the refugee issue. Some think the EU should fence itself off the refugee problem and shut its borders; some think we cannot close our eyes to the problem and its primary source; some blame their governments for inactivity and short-sightedness. Such a difficult situation hardly has one right solution, but it's obvious that one constant must always be kept in mind when dealing with the problem – humanism. These are not just fine words or an attempt to teach someone. This is an obvious necessity in today's state of things in the world.

Subscribe to our mailing list: