Belarusian Dissidents as Nasty as They Wanna Be.

Jacob Davis, chicagocritic.com

By William Shakespeare

Directed and Designed by Vladimir Shcherban

Adapted by Nicolai Khalezin

Produced by Belarus Free Theatre

Playing at Chicago Shakespeare Theater

If you need proof of Shakespeare’s enduring importance around the world, look no further than the Belarus Free Theatre, now at Navy Pier for a limited engagement. Part of the Shakespeare 400 Festival, this production follows the Russian-language Measure for Measure that played here last month. But while Measure for Measure had a relatively simple plot to showcase Eastern European dramatic techniques with, the Belarus Free Theatre’s production of King Lear is more of a commentary on the play than a telling of its complicated story. The artists’ program bios are a long list of persecutions they have suffered for protesting the revived Soviet regime and refusing to submit to government control. Even the fact that the production is in Belarusian carries significant weight in Belarus, which many of the company members are exiled from, and where their ensemble performs secretly. I advise theatre-goers to brush up on King Lear before seeing this version of it, in order to focus more on the specifics of director Vladimir Shcherban’s presentation.

Kiryl Kanstantsinau (Edmund) and Maryna Yurevich (Regan). Production photos by Nicolai Khalezin

Yurevich and Yana Rusakevich (Goneril)

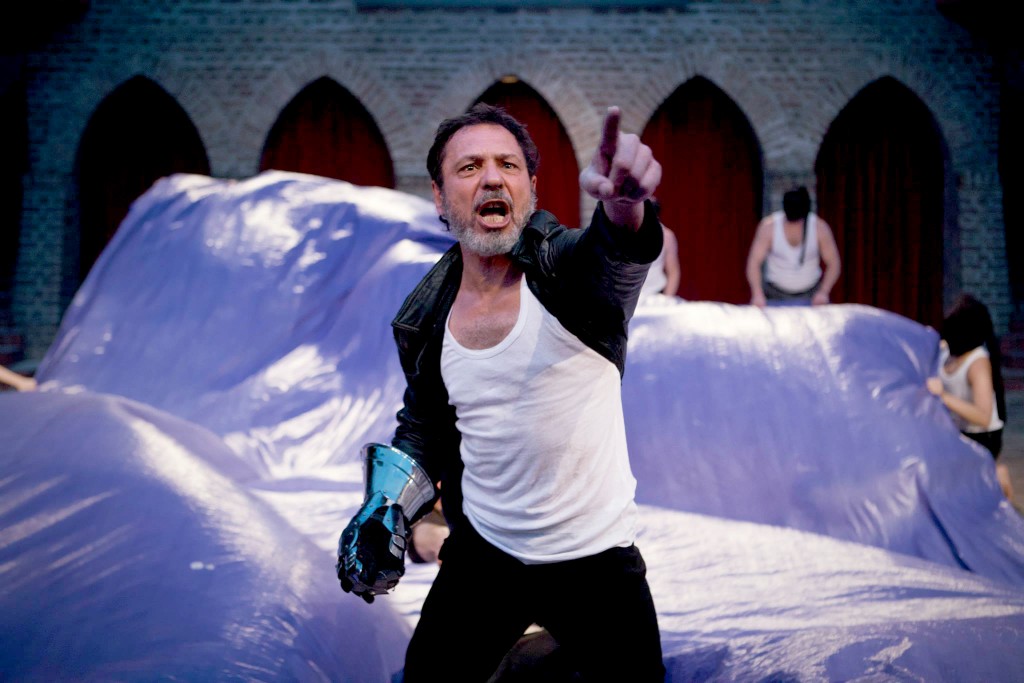

Aleh Sidorchyk’s Lear is a showman. Even before he enters, his court blares jazz and swing music. When he hobbles in, he feigns great age and feebleness before throwing off his wig, to the delight of his entourage. One costume piece he retains, however, is his fearsome gauntlet. When Lear asks his daughters to proclaim their love for him, they each do so in song, with accompaniment from the Fool (Elias Faingersh) on trombone, and the Earl of Kent (Dzianis Tarasenka) on piano. Goneril’s (Yana Rusakevich) dance is highly sexual, our first clue that this Lear and his family have boundary issues, and Regan’s (Maryna Yurevich) is a power ballad she uses to fire up the crowd. Youngest daughter Cordelia (Victoria Biran) is persuaded to sing as well, and her French cabaret-style lament at the inadequacy and artificiality of the pageantry gets Lear very angry. He’d been pleased to scoop dirt into his seemingly adoring daughters’ skirts to symbolize his bequeathing of his realm to them, but Cordelia doesn’t get any dirt. She gets banished.

Sidorchyk and Pavel Radak-Haradnitski (Earl of Gloucester)

Perhaps Lear is so fond of pageantry and fantasy because he and his realm are so shabby and uncouth. Shcherban’s design isn’t pretty. The costumes and props are well-worn, there’s no scenery, and the house-lights come up for long periods. Brecht’s alienation effect is in full force. Though Lear is actually the picture of physical vitality, many of the other characters are disabled or deformed. The Earl of Gloucester (Pavel Radak-Haradnitski) rolls about in a wheelchair, and when he urinates, he demands that his bastard son, Edmund (Kiryl Kanstantsinau), hold a bedpan for him, which he thinks it great fun to miss. Edmund is as repulsed by his father and Goneril and Regan are by theirs and Lear’s retinue, who are unhygienic and have a penchant for gross-out humor, as well as being violent, destructive, and creepy. Not that Edmund, Goneril, and Regan are any less violent, they just prefer a modicum of refinement, since that’s the whole point of having power. Despite their efforts, mire is the order of the day. When Edmund has his brother Edgar (Siarhei Kvachonak) banished on false charges, Edgar fully commits to pretending to be an insane homeless person through creative use of his own excrement. (Chicago Shakespeare warns people with peanut allergies about attending this show, as the scent of this prop is overwhelming even in the back of the theatre).

Aleh Sidorchyk as Lear

Near the end of the play, after the final battle, there is a brief scene with original dialogue as the winning side’s soldiers invent their justification for murdering their captives. I get the feeling that this scene was the entire point of the production, and only afterward do we get see any contemplation or truthfulness from the self-deluding Lear. The execution is particularly disturbing in light of how many times some of the actors have been arrested in Belarus, and their continuing defiance of the government there. The show’s most affecting moments are the dirges the cast regularly has cause to break out in, but there are many other staging devices that communicate enormous emotional tumult, including the famous storm scene. Not everything in the show is abject or grotesque, and the parts which are mostly have strong justifications rooted in this very distinctive company’s vision. The Belarus Free Theatre’s King Lear is designed to make audiences uncomfortable, and perhaps is not the ideal introduction to the text (although simply reading it beforehand should provide sufficient context for understanding Shcherban’s invoking of it). But it is a unique experience, and though the actors speak a language that is uncommon even in their home country, their voices are strong, and they are clear masters of their craft.