Belarus Free Theatre’s theatrical laboratory Fortinbras’ provocations of pop up contemporary art and theatre shone a bright light through the chinks of the armor of Belarus’ dictatorship this past December in a cold and rainy Minsk.

verity healey, howlround.com

Belarus Free Theatre (BFT) pioneer performance inspired campaigning, now, only months after Belarus signed the UN convention to protect the human rights of those with disabilities, Fortinbras’ students yielded the fruits of their own training to mount a series of “public actions, installations and performances across Minsk asking: ‘Why don’t we see people with disabilities around us?’”

"Belarus is in the grip of uncertainty, it stunts itself when it embraces difference with only half hearted measures, it is plagued with anxiety when these measures are tested and are found wanting, it wishes to go forward but is caught in the throes of a dictatorship which forces the country to tread water."

Belarus Free Theatre and Fortinbras stand with the banned and the disabled are banned in Belarus. The theatre’s modes of theatrical practices have grown, by necessity, out of the stranglehold of Alexander Lukashenko’s continuing dictatorship. The time seems right to up the ante, Lukashenko was recently returned to power in what many believe to be rigged elections in October 2015. In a city run by the KGB, the only secret service agency opting to keep its name after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, how can such performance interventions affect the citizens of this oppressed municipal? The answer is to bring the disabled and impaired out onto the streets of Minsk and invite its citizens to look at, see, acknowledge, and accommodate difference. In a country which seems to function as a satellite state, where even the mention of Lukashenko’s name in derogative terms seems sacrilege, the time is ripe for such a move as NGOs and The Office for The Rights of Persons with Disabilities watch, over the next two years, to see how the government will fulfill its obligations set out in the UN convention. It’s a country where 50 percent of its people have said they are ready to integrate those with disabilities, but where 80 percent of those who are disabled are unemployed. You might say, Belarus is in the grip of uncertainty, it stunts itself when it embraces difference with only half hearted measures, it is plagued with anxiety when these measures are tested and are found wanting, it wishes to go forward but is caught in the throes of a dictatorship which forces the country to tread water.

“They don’t care if we are on fire.” Photo by Siarhei Hapon.

Fortinbras’ provocations highlighted these problems. Their performances, taking place on the streets and in cafes and cinemas ruled by an underscoring of fear, drew back the curtain on Minsk’s antiquated infrastructure that makes mobility and taking part in city life difficult for the disabled. Almost no one could escape the projects’ warm embrace, not even the police or the KGB, who became unsuspecting bit part actors in the theatre laboratory’s provocations. Take participating student Masha’s action for example. Roads and highways in Minsk, with their steep curbs on pedestrian crossings, are not able to be navigated for those who are impaired. It takes longer than the time provided to cross the road, leaving the disabled often caught in traffic. When Masha and others in wheelchairs flung themselves out across the highway with a banner which read “If I hinder you, call 223-70-95” (the phone number of the head of the Committee of Labour, Employment, and Social Protection at the Minsk City Administration) just down the road from Lukashenko’s aptly named brand new Independence Palace, a police officer, to an audience of curious motorists, huffed and puffed to push them back over the steep pavements. It took him a few moments to achieve this. If only the pavements had a gentle ramp, it would have been easier. “The real reason why Minsk is not adapted for disabled people is lack of money and a low priority of the disability issue when it comes to the distribution of funds,” Ministry of Counterculture reports.

What’s the solution? Disabled people should not cross the road here, but use the subways only? That might work but the ramps down into them are very steep. “No matter” said some KGB officers as they were trying to prevent student Alex from staging his project Boulders and Obstacles. Whilst two officers arrested Alex and took him off for questioning, others assisted a wheelchair-bound participant by lifting them down one of the ramps, as if to prove that they were navigational. But what happens if no one is around to help and the disabled person is alone? “Oh, just call the man,” they said. What man? We looked around but there was no “man.”

As the hours of the performances stretched out into late December, the disabled participants and Fortinbras ratcheted up the momentum. It felt like it was Fortinbras versus the state with an audience looking on. During Veronica’s project, to promote the idea that disabled people are no less beautiful or capable of wearing fashion as everyone else, a melee of security guards descended on eight people sitting in wheelchairs in a shopping mall. “It’s a public space,” they said. “Yeh, exactly, a public space,” Fortinbras answered back as shoppers stopped and stared. It became apparent that the authorities like to think that they are in control, yet, typical of a soviet country, their apprehension conveyed the chaos behind the deceptive calm. In a cinema foyer, all hell broke loose as a student distributed leaflets about the campaign to members of the public. Fear: of not being in control, of being in the power of others, of facing something unusual and not knowing what to do, exuded from the female security guard as Fortinbras tried to make their point that deaf people, and the hard of hearing, should have access to subtitled films. Two young men sitting outside the cinema had no such qualms, they commented that they have “Some friends who are deaf but they have their own social group and don’t use the cinemas.” This echoed organizer Stanislava Shablinskaya’s statement that the impaired “Live where they know their routes, know how to get to a shop or work. We don't see them, because the city is not adapted for them.” Having spent most of their lives living in a dictatorship, the younger generation seemed able to empathise more. This conflict of generational attitudes showed itself to be an undying theme. When disabled participants wrapped themselves in clingfilm outside the Museum of Art, creating a finite chrysalis from which they could never break free, a metaphor for how they can’t quite join in the life of the city or Belarus, a much older woman muttered “ Don’t tell me about things like this, I know better than you!” A little like the reaction of an elderly man towards the project Blind and Braille, where he labeled blindfolded students trying to find their way on Independence Avenue as “Devils.” But a young man on a bike could not drag himself away from the clingfilm spectacle. He told us he had just moved back from Berlin, where disabled people had all the facilities they needed and were fully integrated into the life of the city. Why not here? “People who are disabled have a right to a normal life and should have equal access to public spaces” another young woman said boldly.

Blind and Braille Project. Photo by Siarhei Hapon.

Wheelchairs wrapped in clingfilm. Photo by Siarhei Hapon.

“We can’t comment, if you want to make a complaint please write a letter to your local police station” was all the KGB could answer. They had been hanging around with us on the streets of Minsk in the cold and rain for hours now. At least they were talking; when they first arrived they stood silently, taking little photographs, their cameras roving over our faces. When the public taxi for disabled persons turned up, they helped the driver lift the people out of their wheelchairs and into the seats. There were no ramps or lifts for the wheelchairs. No one asked if there was a particular way anyone should be carried. And how were the KGB to know that only one of the group was actually disabled and everyone else was just acting? Nonetheless, they kindly highlighted the mobility difficulties faced by disabled people in Belarus everyday.

Christmas parade. Photo by Siarhei Hapon.

Some eleven actions later and Fortinbras weren’t done. Specific projects like “I want to pee” brought to people’s attention the lack of services for the impaired, yet the task of integrating the disabled participants into the actual life of the city was still to come. At first, it came through improvisation. To rid ourselves of our KGB friends and to get out of the rain, we dashed into a wheelchair friendly cafe. But whilst its exterior entrance ramp seemed promising, chaos ensued inside as we blocked narrow passageways and paths wholly unfit for anything other than the able-bodied. It was Christmas Day and packed with families who gawped at this small army of disabled people. However, the managers raced to help us, proving that not all of Minsk’s citizens accept the attitudes of the state. Integration was likewise the name of the game as wheelchair users, dressed as Ded Moroz and Snegurochka, tried to join Minsk’s annual Christmas Parade of Grandfathers Frost and Snow Maidens. Whilst young policeman in military fatigues clutched batons and told us that they were “Under orders to stop anyone in a wheelchair from joining the parade” at the other end of the extreme, when we had outrun the police and caught the end of the march in Liberty Square, children sat on the disabled persons’ knees and gave them sweets, their parents looking on and taking photographs. All were normal if normality could be allowed to just be. “I feel alive!” one disabled lady shouted to me, her exhilaration and joy at finally being able to take part in the life of the city bringing a wide smile to her lips. Sasha too, a young man who had broken his back in an accident in Norway, could not stop smiling.

"Misha, walking out into the center of Liberty Square at the culmination of the parade, his hands alight and wearing a placard which said ‘They don’t care if we are on fire’ to promote the plight of deaf people who have no access to the emergency services, was engulfed by media and the public, all with the same question: why are you doing this?"

The success of Fortinbras’ provocations was measured in how they fluidly targeted and interpreted the reactions of the authorities and used them to further the power of their messages, combined with the reactions of the public and the press. Misha, walking out into the center of Liberty Square at the culmination of the parade, his hands alight and wearing a placard which said “They don’t care if we are on fire” to promote the plight of deaf people who have no access to the emergency services, was engulfed by swathes of the media and the public alike, all with the same question on their lips: why are you doing this? “I stand for deaf people,” he said. But as he talked, he was suddenly yanked away by another student and I found myself and my translator running fast towards BFT’s jeep that pulled up, out of nowhere, beside us. The KGB were in pursuit, but the world did see. Even if it was not reported. Later Misha was identified and contacted by the police; BFT’s lawyer advised that he cooperate or the situation could get worse. In court he was given the choice of a 180 euro fine or a jail sentence for "organising disturbances at public places and events.” As he said to TV news crews though, he was not hurting anyone.

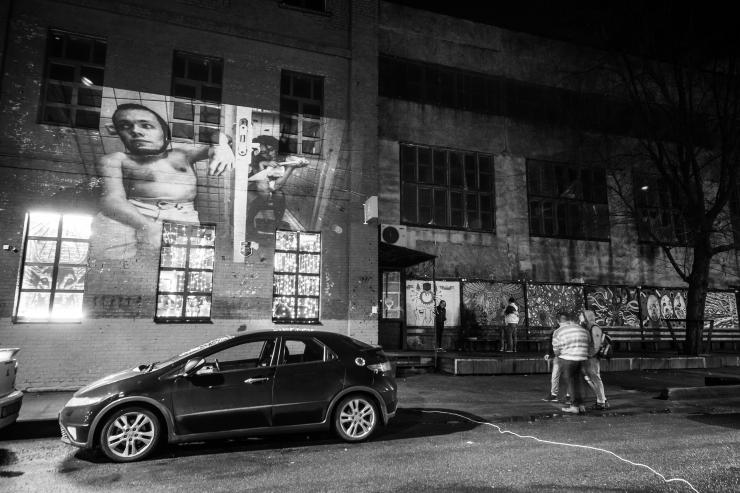

“I- we- don’t want to offend people but Belarus can’t accept difference,” Natalia Kaliada said to me shortly before I went out to Minsk. So we come to Darya and photographer Nikolai Kuprich’s project. A series of stunning black and white photographs, in documentary style, of disabled and able-bodied gay people in intimate relations with each other, were projected onto The Republican Unitary Enterprise National Film Studio “Belarus Film” and other buildings. As well as beauty, there’s an inherent criticism of the state projecting out from the images. Same sex activity is not illegal in Belarus but being homosexual is still highly taboo and anyone who comes out could face harassment and abuse. Whilst Misha’s flaming hands, held out as if he were a guardian angel, will be an enduring image of the project, the faces in Darya’s “Coming Out,” those who had found acceptance and commonality with each other, though not with the people of Belarus, should forever haunt Minsk’s citizens.

Coming Out. Photo by Nikolai Kuprich.

The provocations were a game changer. It rewrote the relationship between Fortinbras, BFT, and their public and the secret services. It had an emotional impact on its audiences—the authorities included. It also took advantage of the state’s attempt to control as a way to illuminate cracks in Lukashenko’s dictatorship. There were two forces struggling here—Fortinbras’ desire to integrate the disabled into the life of the city and ask the citizens to embrace difference, and the authorities desire to ghettoise that difference and therefore encourage suspicion. But Fortinbras have shown Minsk how it can be done. In the end, the message, both from Fortinbras and many of Minsk’s citizens, especially the young, could not be clearer. How to cope with difference? Embrace it.

Subscribe to our mailing list: