Rare meat, naked actors, Vladislav Kovalev's child photos – Belarus Free Theatre shows Belarusian version of Trash Cuisine in Minsk.

Alaksandra Dynko, Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty

“Minsk is a city of the culinary heaven,” chef Pavel Haradnitski welcomes the audience. “Zlatka”, “khadun”, “romantic cutlet 'fern flower'” – the trash cuisine chef interlards his speech with familiar names of Belarusian fast food dishes as he introduces recipes of another sort to every supposed owner of the book '400 Potato Recipes'.

“You will taste these dishes and understand how easy it is for you to repeat all these tempting recipes here and now,” the chef promises.

As in the real kitchen, the show guarantees the breathtaking hell of tastes, smell, music and movements. At the end you will be made to cry, literary, even if you don't want it. Belarusian audience hasn't experienced anything like that yet.

Do you know that the current is turned on twice for a minute with a 10-second pause in an execution by electric chair? If a person is still alive, the current must be turned on again, and no one knows how painful it is? That those sentenced to death in Thailand were killed by a machine-gun firing squad, and an execution by stoning takes two hours? That some people sentenced to death in a gas chamber spend hellish minutes before they die?

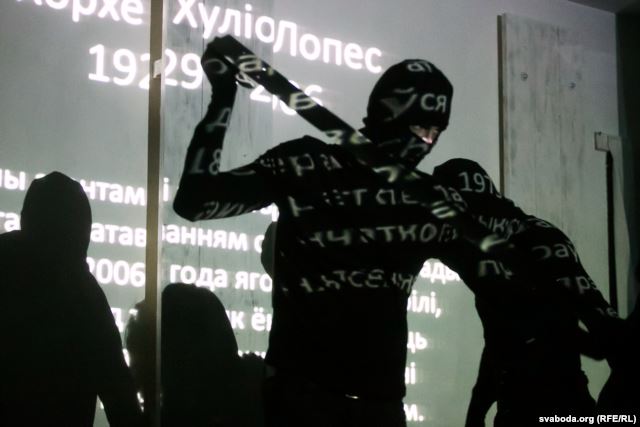

BFT's actors present different types of murder through a sophisticated body language, and you can see in these polished accurate movements that people put as much their heart, fantasy and national traditions in the procedure of taking someone's life as in cooking their favourite dishes.

The book '400 Potato Recipes' can be found in any kitchen in the state that kills an average of two people a year. And you have it too, you, a citizen of the only country in Europe that uses the death penalty.

The idea to combine cooking and murders belongs to stage director Nicolai Khalezin.

“It is about the process of destruction that can take various forms. It is typical both for cooking and murders,” actress Vika Biran says. “I am sure that it's possible to find good cooks with their own uniform and special recipes, and the same is with murders. It became clear when we began to study details of executions – their various types, rituals, bells and whistles...”

Colonel Oleg Alkaev visited actors to show the “Belarusian” murder recipe.

“We held an experiment. He appointed people: you are a deputy prosecutor, your are an executioner, etc. I was chosen to be a victim,” Vika says. “Alkaev watched what we were doing and said, 'the body falls down in this way, you did it wrong, the body usually falls down like that.'”

Colonel Alkaev was in charge of the firing squad in Belarus. He says 134 people were killed during that period. A video with him was added to the Belarusian version of the show.

“He [the person on the death row – Radio Svaboda] is called to the next room, where an executioner with a handgun is already waiting for him, two men make him kneel, the executioner shoots him in the head. It takes only few seconds. He thinks they are taking him to a car, but they are taking him to an execution,” a man with grey hair tells about his job calmly and consistently.

The actors on the stage depict hookah bar visitors and move their lips, imitating his speech. These are the same people who gave 80.44% of the vote in the 1996 referendum in favour of capital punishment, and thus made this shot in the head possible.

Belarus Free Theatre studied traditions of the “legal murder” in Ghana, Malaysia and Thailand. The story of Liam Holden, a man who confessed to a murder under tortures and was sentenced to death, is told with the help numbers projected on the screen that can easily be taken for ingredients. “17 years Liam Holden was in prison… 29.3% of his life was spent in prison.”

They brought a story about the Rwandan genocide from their trip to Africa. The chef cuts meat with a big knife, almost a machete, and roasts it. Actress (Stanislava Shablinskaya) plays a Tutsi woman and says how her Hutu husband murdered, cut and roasted three their children. And then her. Each serve is his own child killed on the order of the Rwandan temporary government.

“I do not love any of you,” the Hutu father (actor Kiryl Masheka) says indifferently, sitting on the floor amid crushed peanuts. The room smells of roast meat and hot blood.

“I want to cry all the time I am on stage,” Kiryl says after the show. “But I can't sit and cry. I'd like to, and it makes me feel even worse. I have many exits, I go behind the curtain, breathe out and return on stage.”

“The nature of violence is the same everywhere,” actor Pavel Haradnitski thinks. “What happened in Rwanda could have happened everywhere, in our country too, under certain conditions.”

“It not only could have happened, it really happened,” actor Andrei Urazau adds.

Trash Cuisine is one of the most successful shows in BFT's abroad career. It was played with foreign actors in English in London, New York and Amsterdam. “A culinary journey around the circles of Hell on Earth,” RFE/RL's Belarus Service (Radio Svaboda) wrote about the Amsterdam premiere two years ago. “Raw fare for strong stomachs,” The New York Times wrote this April.

“It would be dishonest not to show the performance to Belarusian audience,” BFP's representative Sviatlana Suhaka says to nearly thirty Minsk residents who came to watch Trash Cuisine ahead of Christmas, on Wednesday December 23.

The Minsk version differed from the original one. All actors were Belarusians, three of them took new roles, and three new actors were added to the cast. The troupe had to stage the large-scale (by theatre standards) show in a room 6 by 6 metres in Minsk. But the theatre, for which the world's most interesting venues are open, remains underground in its homeland.

Experienced spectators began to listen to sounds outside from the first minutes of the show, expecting the stamp of military boots, the sound of the broken doors and the shout “Stand against the wall, hands up!” It seemed to me for a long time that only I felt it, because the police had already arrested me at BFT's show. But it appeared after I spoke to other people that almost everyone expects these sounds and shouts.

“We are all paranoid here,” manager Nadia laughs. She is happy that a year ago BFT got the place available “24 hours a day”. It is a warm two-storey garage almost in the centre of Minsk. Audience members are still given instructions how to get to a meeting place and accompanied to the location in pairs.

“Sometimes we see in our audience the people who are not our audience. They are from the 'other side'. They do nothing, but they look suspicious to us. They watch the performance and leave. We know that some of our audience are sometimes invited to conversations, like 'what were you doing there, would you like to work for us a little, you will watch their shows and tell us what's happening there,'” Nadia says.

What is happening there is that the story of, perhaps, the most famous Belarusian sentenced to death, Vladislav Kovalev, is told through his mother Lubov's words, his child photos and heart-breaking sounds of Kupalinka song.

“Many believe in what they've read in a newspaper,” says actor Siarhei Kvachonak, who plays Kovalev in the performance. “They say 'yes, they [Dmitri Konovalov and Vladislav Kovalev organised the terrorist attack on the Minsk metro in 2011, according to the official version – Radio Svaboda] are killers, we hate them.' I'd like them to think. I know his mother's words, I saw her, I talked to her, and I'd like to make people understand that maybe something wasn't so as we think. There's something strange that the guys were executed in the first year after the attack.”

“I don't excuse them,” Siarhei adds. “Maybe it really happened, maybe not, but I think it was done very quickly and very hastily. I talked to his mother, I don't believe they had exploded the metro. I want audience to think about it and make some conclusions.”

“The show provoked admiration and disgust,” a young woman shares her impressions after the performance. “As for the death penalty, if we speak about my personal position, I'll perhaps say like an average person who has never been affected by it personally. I think most people don't have their opinion on the issue.”

“I understand that the real miscarriage of justice is possible. It's not The Shawshank Redemption, it takes place here,” Pavel Haradnitski says. “We see many dark places in Kovalev's story. It would have been logical to continue the investigation. But 'one, two, three' and these people don't exist anymore. Our laws allow it. If the death penalty were not allowed, they would have continued the investigation, thrown them into prison, gathered proofs...”

'One, two, three' – we hear sharp knives chopping on wood in Trash Cuisine. The kitchen mustn't cool down, it constantly needs new ingredients. Twenty eight thousand people were killed with machetes in Rwanda in three days; six more people were sentenced to death in Belarus after the Kovalev-Konovalov case.

“I read in an article how a member of the Soviet secret police NKVD executed ten or twenty thousand people,” actor Siarhei Kvachonak said. “I was thinking yesterday how such a person could live quietly until retirement. I don't know how it can happen on Earth.”