San Miguel was born in Brazil, in Colombo – a community of former slaves – which is a two-hour car ride from Rio de Janeiro.

His ancestors come from Africa. White plantations owners, who moved to Brazil from Europe, first tried to make slaves of the local population – Indians. But this undertaking came to precisely nothing: the freedom-loving Indians would rather bring themselves to death than become slaves. Then it was decided to bring slaves from Africa, and the whole industry started using them.

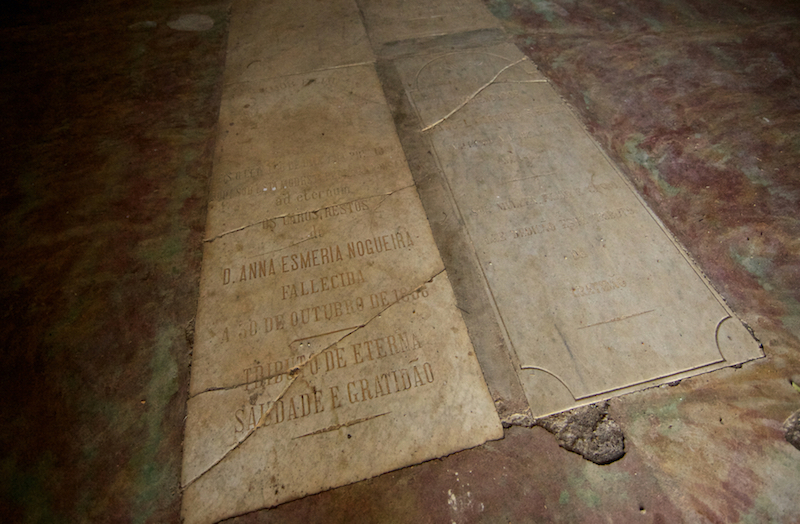

San Miguel’s ancestor was purchased at a slave market in Angola and taken to Brazil, where he belonged to a Portuguese aristocrat whose family had moved here from Portugal. In 1888 princess Izabella issued a decree to abolish slavery, and the baron, to whom this land belonged, acted nobly, and gave it to his slaves, who had served him with good faith and fidelity for years.

The name of San Miguel’s direct ancestor had been put into the land registry, so he came into heirdom after the death of his father. But it turned out that not all was unclouded in the life of this family since the very first day of owning the land.

After the land was passed to the former slaves community, there were quite a few of the willing to grab a piece of the huge plot. The former slaves had no law experience and no idea of the litigation mechanisms. More advanced neighbors made use of that and, by hook or by crook, would grab land pieces whether by the service of corrupt judges, or through the simple-heartedness of the slaves. Sometimes it would go as far as a hectare of land being given up for a bag of kidney beans in a lean year.

At some point this stopped, and the situation stabilized. But in the late sixties, one of the local farmers living near Colombo bribed a judged and registered 880 hectares of the community’s land as his. In one day the community members had lost their land, - even the where their houses stood. Litigation started, which has been going on for half a century already.

In 1999, Rio de Janeiro authorities made the decision for the lands to be returned to two communities – Caminho and Colombo. With the former, the court acknowledged the the government decision quickly, but for the latter it is ongoing. The incumbent judge made the decision that the case for the land was legitimate, and the government could pay a compensation to the community should they wish to do so.

It was only in 2011 that San Miguel won back the right to live in his own house – the house where his children were born, where he was born himself and his father before him. As a result of arbitrary rule by judges, San Miguel’s family’s plot of land has been cut down to 1% of what it was.

San Miguel’s family survived because of the small planted areas that remained in his possession. They were located on hillsides, and it was an incredibly difficult job to cultivate them. But twelve years ago a law was adopted which forbids the cultivation of crops on areas located on hillsides of over 45 degrees atilt. With this, San Miguel’s family lost the last opportunity to feed themselves, and he started looking for a job.

This task turned out not to be an easy one: despite the fact that San Miguel is a person of incredible diligence and integrity, none of the farmers wanted to hire him due to the litigation.

In order to understand why no one wanted to hire San Miguel, we need to go back in time. For this is a conflict that goes a confrontation between a former slave-community and a farmer who had illegally seized the land.

In 2003, San Miguel brought the community members together and urged them to openly express their opinion on the land seizure and corruption in judiciary. Right after that a whole range of threats followed, addressed to San Miguel and his family members. Strangers promised to deal shortly with the community members, unless he stopped the activity.

San Miguel did not stop the fight for the land, and a whole series of attempts on his life started. For the first time he faced that as he was riding a motorcycle on a highway. At some point he got squeezed among four cars trying to knock him down. By some miracle he avoided death. Next time he was shot at on a highway, but death passed by, again by a miracle.

Several times San Miguel noticed crossbows installed along his route over the hills, set to go off on the break of a string, if a leg brushed against it.

Once, the family were almost poisoned. San Miguel’s daughter came to school, and a neighbors’ boy, foolish by birth, overwhelmed her by saying “I poisoned your water today”. The daughter rushed home and managed to warn the parents before any of the family members took a drink from the reservoir-storage. The community members forced the boy to publicly admit that it was him who had done that.

Another time, a direct attack on San Miguel’s house was fended off by the community members, who bravely stood in defense of their leader, whose authority is unshakable here.

The influence of farmers have on the tenor of life in the region is huge. This is why those, who fall in disgrace with them, lose any possibility to make a living. Everyone refused to hire rebellious San Miguel regardless of his capability and high level of professional training. The nearest job he found was a two and a half hours walk from home. He takes the route six times a week to work a ten-hour day at a farm.

Church also put pressure on the commune of former slaves – the local regional bishop claimed that the community was unworthy of having a parish with the Catholic Church.

When you are in Santana, you feel that the time has stopped here. As if it is not the XXI century around, but the times of San Miguel’s childhood, when he started working at the age of eight. Farmers then would hire adults only if they could bring their children as additional free labour force.

Even if slavery has not remained slavery as such, it still exists, it has changed its form, and poses as something new. San Miguel told us how, in the times of slavery in Brazil, slaves were made to eat out of a common trough with their hands, and even his mother’s generation could not break the habit of eating without the use of cutlery.

As we were speaking with San Miguel in a city square, a local drunkard approached us and asked him: “Where are you from?”. He said he was from Colombo. “Ah, this slaves’ place”, – was the response. The word “slavery” is still in use, despite the fact that over 120 years has passed since its abolition. There is a legend in Santana that here lives an owl with human eyes that leads people astray. It looks like it really exists here without ever taking a break from playing its trick.

Subscribe to our mailing list: