Belarus Free Theare’s Fortinbras theatre laboratory has selected students for a new two-year programme. Fortinbras is the only arts educational initiative in Europe training new cast members for a theatre while working almost underground. The drama course in the programme starts not with writing plays, but with immersing in journalism, which is a new experience for many. Students’ works created during the course are published by various Belarusian media as part of the social campaign Citizen Journalism.

This year’s course has an unusual start: when studying the interview genre, students said they’d like to interview Nicolai Khalezin, Fortinbras and BFT’s artistic director. He agreed, on one condition – questions mustn’t repeat those he has answered during numerous interviews over the past two years.

Nicolai Khalezin

Vadzim Kaloshkin | A sort of existential question: Who are you?

This is the question I don’t answer to myself out of principle. It’s the same with the questions “Who is to blame” and “What is to be done?” I had a period of navel-gazing and made attempts to dig into philosophy looking for answers to rhetorical questions, but I understood quickly enough that life is short and I’d like to do something important, while searches for answers to eternal questions may never end. Perhaps, the only indisputable truth in the answer to this question is that I am a mammal as I was born live and fed by milk.

Dzmitry Mitskevich | In an interview with Alexander Molchanov, you said that theatre is archaic and not interesting. Why then do you still work there?

In this particular case, the question contains the answer. It is the archaic nature and backwardness of theatre that makes it an ideal platform for creative innovations we use. Despite the stereotype, Belarus Free Theatre is famous not because it exists in a not free society or within the creative resistance we declare, but due to the groundbreaking approaches that expand the representation field and give birth to a great number of followers. It’s scarcely possible in a highly dense innovation environment of cinema or literature, where a lot of experiments stay outside the field of the audience – not only a wide one, but also a narrow professional audience.

Let me give an example from life in Belarus. A few days ago, I finished reading Alherd Bakharevich’s not yet published novel Dogs of Europe and understood the book is written at an incredibly high level, both stylistically and creatively. At the same time, I understand that it’s hardly possible to present it to the world community at the same high level it was written due to translation problems. Instead, we can show it to the world through that archaic theatre, where it could sound loud, innovative and well articulated, which, by the way, could increase interest in the original.

Belarus Free Theatre pays much attention to text and acting. Have you ever thought of a project without actors or text? What do you think about companies like Rimini Protokoll?

We have different performances. They differ also by the amount of text. For example, Red Forest has a minimum of text and focuses more on visuality. The final part of Burning Doors contains no text at all. The same is with Numbers, the third part in the performance Zone of Silence. I like the idea of not using or using as less text as possible, and I am becoming stricter as I’m getting older – I cut out all text that doesn’t work for the plot. But it seems weird to me to abandon acting. It’s probably because since I have been watching theatre productions, I’ve seen only two successful scenes in which a director didn’t use actors. One of them was in a performance by a German theatre. The final scene of love confession and death was played by two robots, each about 40 centimetres high. It was so realistic and moving. Also, it added new meanings for reflection. The second scene was in Romeo Castellucci’s performance, in which wigs were coming down from above and winding round a spinning rotor at a huge speed. The audience couldn’t get their eyes from the process. But these are complementary scenes and not entire performances.

We are friends with Rimini Protokoll. I like them. Like most theatres, they have strong and weak productions, but they chose the right strategy. They’ve developed their own creative approach, and other theatres risk becoming “a second Rimini Protokoll” if they try to repeat it.

Don’t you think that making protest aesthetics mainstream kills its nature, that it’s a local rebellion built into control mechanisms and it has no chances of getting over them? Do you think it’s possible to speak about serious issues without touching on mainstream events?

I’m convinced that any properly developing process brings a product to the mainstream area, whether it be a music band, a theatre company, an idea or a social movement. Otherwise, it remains in a marginalised niche and doesn’t affect social consciousness. Yes, we can say that Jimi Hedrix’s music of the period when he played at Cafe Wha? for a couple of hundreds of regulars had its charm and energy, but for me personally his prominent performance at Woodstock in front of tens of thousands of fans was far more important as it formed an army of musicians who followed him and made the world learn another, alternative nature of guitar music.

For me, it’s important to form a “guerrilla squad” that brings provocative ideas, thoughts and meanings to the mainstream area while formally being its part. I can recall the musical A Chorus Line as an example. At first glance, it’s a typical musical with rather predictable plot devices and a clear musical framework, but it has a social “bomb” inside its dramaturgy that explodes plenty of themes – from a woman’s loneliness to problems of black people and LGBT. When the musical won the Pulitzer Prize in 1976, many asked: how did it happen that a performance in such a “light” genre did not only become a social event, but also sparked a wide public discussion?

Aramais Mirakyan | Which production was the hardest for you, morally?

I think Burning Doors was the hardest piece to work on. We had a number of problems and challenges. Firstly, we worked with Masha Alyokhina, who is not a professional actress. You want to optimise the creative process and do as much as possible in the shortest period of time, but you have a person who has never worked in theatre. You slow down, spending time on what your actors learnt ten years ago. You grit your teeth. It looks like all runners have started off, but you have your shoe stuck in the starting block. You are short of time – you have thousands of dollars of expenses every day and unfinished scenes… In the end, what saves you is the thing on which you’ve spent much effort and time – management. It turns out that actors who’ve been working with you for many years mobilise themselves at a certain point and become mothers and fathers, coaches and doctors, towers of strength and lifesavers. They take care of a newbie, trying to help both her and themselves. Finally, you all gain a victory.

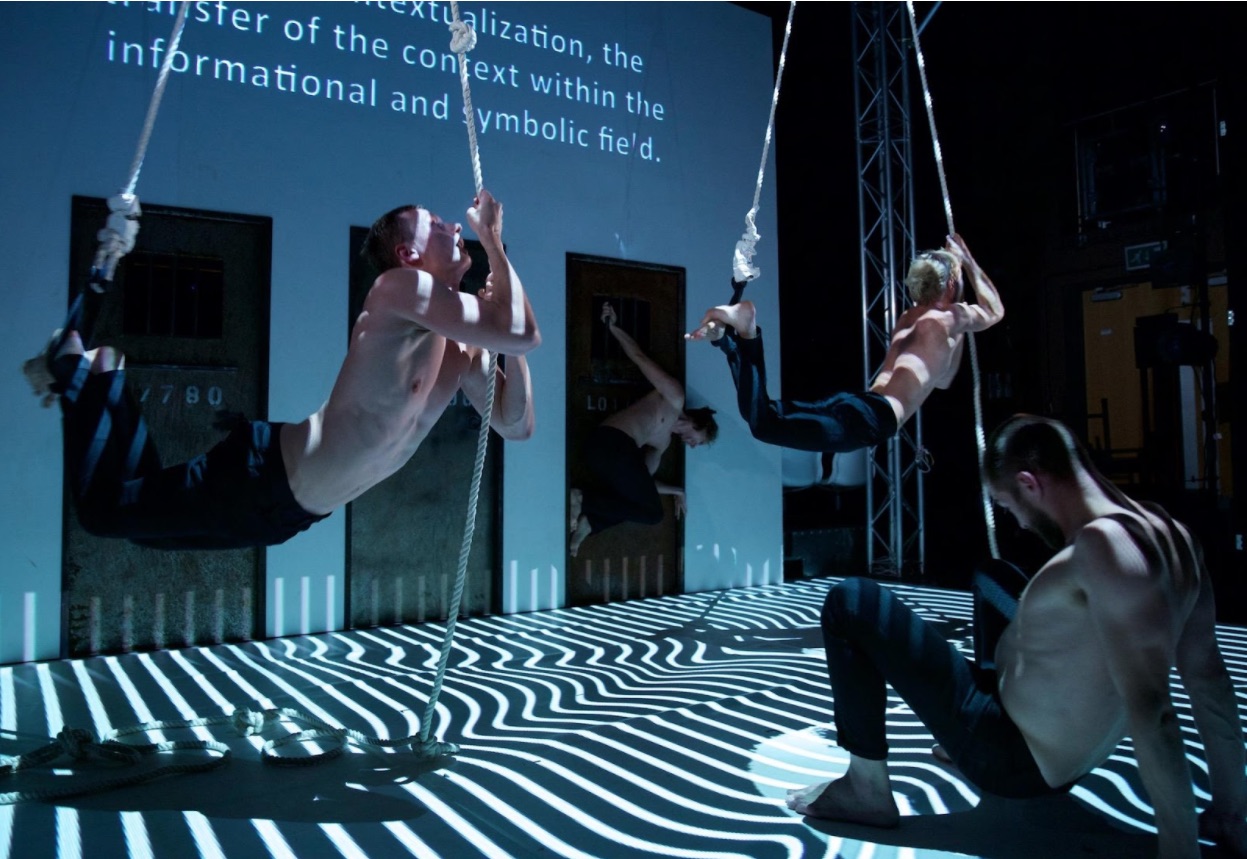

A scene from Burning Doors

Another difficulty was that the characters in the play have their “heroic trail” – books, articles, films about them… It is how the audience wants to perceive them. You task is to distance yourself from them, equate them with executors, find their weak spots in addition to strengths. You need to build a performance as a battle field of personalities regardless of their sign – plus or minus. If you don’t equate a protagonist and an antagonist, you always risk failing to build a system of artistic images and finding yourself in the area of propaganda posters.

In this performance, we set a creative task of finding limits of actors’ physical abilities. This is the task no one has set as a system in world theatre. When we approached certain limits during rehearsals, actors tried to push them further away. On the one hand, it’s amazing, but at a certain point, when limits are reached, you must be strong enough to stop – we are a theatre, not soldiers of the Guinness Book of Records. It was a serious moral choice – when to ban actors from moving further and thus stop the creative process.

You’ve recently written: “Theatre has found itself on the remote fringes of social processes. It is a subject which hasn’t understood still that it’s not its place in society that changed, it’s the coordinate system that changed, having removed all groups, communities, alliances and subjects unable to realise the new reality.” Will world theatre be able to regain its place in the contemporary context or its time is expiring irreparably? Are the any theatres in the world, apart from Belarus Free Theatre, whose productions are always surprisingly relevant to the current context?

It’s most likely that theatre will undergo a certain period of understanding and will try to make sense of what’s going on. The question is when it will happen. I’m not optimistic about it. The problem is not only that theatre is technologically slow or has a complicated inner structure. The problem is that there are only few specialists with a political vision in world theatre. In cinema, literature, contemporary art, the rate of such people is several times higher. It would take much time to explain the reasons, but to be short, the root of problems is in the theatre education system and its imbalance with a focus on traditional art, which can be seen everywhere in the world.

Collectives analysing relevant problems constitute only a small percent of all theatres across the globe. There’s an even smaller number of those who combine relevancy and a high artistic level. Without much thinking, I can recall a company that would rely exclusively on contemporary dramaturgy, for example, London’s Royal Court, but I doubt I can recall a theatre addressing today’s control points as consistently as Belarus Free Theatre. There are several reasons. Firstly, making relevant theatre is dangerous. I mean financially, not physically: such a theatre can’t easily find means of living; most sponsors and investors want to deal with a theatre that doesn’t risk. Secondly, as I’ve already said, you should have a political vision and know details of political and social changes taking place in the world. Thirdly, in stable democracies, theatres don’t have an intense desire to discuss relevant social problems all the time. However, the absolute majority of companies in theatrically developed countries address relevant issues from time to time.

Palina Adashkevich | Can we say that provocation as a method is devalued in art? Don’t you think that today’s audience has become immune to provocations, that it is more prepared for experiments on stage?

We can’t speak about devaluation, because art has only two missions: to entertain and to provoke. Or, in rare cases, to do both things together. But I don’t argue that the audience is more prepared for experiments today, because the world is changing rapidly and supply significantly exceeds demand in art. There’s one more “but”: audiences are developed and educated only in the countries where theatres make experiments. Unfortunately, the number of such countries is next to none.

A scene from Trash Cuisine

Can theatre encourage audience members for actions to change themselves and society?

Theatre can encourage both a particular audience member and communities to take action. For this, we must meet a combination of several key factors, each of them requiring what can be described as “very accurately”.

1. A theatre company must find the right social pain point very accurately. It should be based on a serious analysis of the current situation rather than on personal fantasies and stereotypes.

2. Dramaturgical material must be selected and developed very accurately and carefully. It should raise questions that would hit the pain spot. It must be questions, not answers.

3. A director and actors must arrange a performance very accurately with a focus on the problem. It relates to creating images, acting and building the performance’s structure.

If everything is done accurately, the performance can attract press and critics, who, in turn, will launch a discussion in media, which will affect both society in general and individuals. We know from history that theatre sometimes had a direct impact on society. When Poland’s communist authorities banned a performance based on Mickiewicz’s Dziady in 1968, students began to protest. The Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia started with an actors' strike.

Volha Ramashko | What do you appreciate most in actors? Speaking about actors, what would you never forgive?

I appreciate the desire to work hard. I fully agree with Mstislav Rostropovich, who once said: “There are damn many talented people, but only a few are able to work”.

I can forgive an actor most things except for laziness, negligence, unwillingness to improve their skills, a derogatory attitude towards the audience and disrespect for partners.

Ivan Azhhirei | There are directors who work both in theatre and filmmaking. How interesting do you find modern cinema? Under what condition would you like to try your hand at filmmaking?

I find cinema interesting like any art. I think I know it rather well. I receive regular proposals to work in filmmaking, more often as a screenwriter and sometimes as a director. But I have my previous experience behind me. I have never worked for anybody except for myself apart from a couple of years at the start of my career. I am familiar with cinema well enough, I have dealt with it several times, but I can’t say it’s comfortable for me. I agree with most British actors, directors and playwrights who name theatre as the key place to realise their potential, leaving cinema on the fringes of their interests and regarding it as a tool for solving financial issues.

I have a number of ideas for movies. I think they are not bad, but producers will never agree to my conditions. I mean giving me carte blanche – from a script and casting to choosing locations and editing. As producers will never agree to it, I will continue working in theatre, doing what I want and in the manner I want, waiting for the time when I can implement one of my film projects on my own.

Raman Shytsko | Have you ever thought of launching a video blog on YouTube?

This idea comes to my mind regularly, but I dismiss it every time. It’s not because I want or don’t want to do it. The matter is that I am a perfectionist. If I want to launch a video blog, it must have high quality in what regards its content, style and development strategy. It requires much time, which I don’t have yet, unfortunately.

However, I am moving forward in this direction. Next year, we plan to release my interviews with world-acclaimed figures for the post-Soviet audience. We’ve already made a pilot, in which I talk to Jude Law. It is a big interview of around 40 minutes. If things develop as we expect, we can present interviews of the first season early next year.

It’s a trend now that theatre goes beyond the stage. The boundary between actors and the audience is becoming thinner and thinner and sometimes disappears at all. We can see it clearly in BFT’s productions. Where’s the boundary between a theatre performance and performance art, in your opinion? Does it exist?

The boundary between a theatre performance and performance art will never disappear, as these two subjects of the art field are of different nature. A theatre performance is a complicated technological chain and has a sort of “circulation” – it is performed many times. Though performance art can be technologically complicated, it doesn’t suppose repetitions. In a theatre performance, an actor plays a role, while in performance art, an actor remains himself. In a theatre performance, the audience is separated from the stage by the “fourth wall”, while performance art is immersive, giving the audience the feeling of being here and now. A theatre performance has a rigid structure, while the structure in performance art can change in the process.

Of course, times change, and we can speak about blurring boundaries. I mean not only definitions, but also genres, styles and formats. We see attempts to erase the boundaries between performance art and a theatre performance since performance art was born. In my opinion, it makes sense to focus on the expansion of the interactive component of a theatre performance to its limits rather than on the blurring boundaries. It’s for a reason that interactivity in theatre is the most popular topic at theatre conferences that explore and promote innovations.

Hanna Zhahalava | Belarus Free Theatre performs not only abroad and in Minsk, but also in smaller towns across Belarus. What’s the difference between the audience in Minsk and unspoiled audiences outside the capital?

If we take countries like the UK, Germany or France, you don’t see any difference in how audiences perceive a performance. It’s because the theatre infrastructure is well developed there. In Belarus, Minsk’s audience differs not only from that outside Minsk, but also from audiences of different towns. Minsk’s audience is more disciplined, people don’t show much emotion. In smaller towns, audiences show spontaneous, more open, brighter reactions to what they see on stage. They are less skeptical, they have more trust in actors and theatre in general.

I like small-town audiences for their readiness to believe in the truth of theatre. But it also forces theatremakers to be more responsible in order not to kill this illusion of honesty in the actor-audience relationship, which sometimes is not an illusion.

Aliaksei Zhuraulevich | What funny incidents from working on performances can you remember?

Funny incidents in theatre are common, because the human factor plays too big a role here. They become funny and amazing a long time after they happened. Something funny is in any case a failure of the smoothly running mechanism. It causes enormous stress for the collective.

For example, we had the world premiere of Zone of Silence in Thessaloniki, Greece. A speaker we used as the radio failed to work at the right time, and the song we planned to playback didn’t start. Dzianis Tarasenka, who was behind the curtain preparing for the next scene, grabbed an accordion and played the song live. The problem was that he was half-naked in the previous scene, but his next scene required him to be fully dressed. He was unable to get dressed, because his hands were busy with the accordion, so actors were dressing him up while he was replacing the pre-recorded soundtrack.

A scene from Zone of Silence

Among the latest incidents is one during another world premiere – Burning Doors in Leicester, England. Andrei Urazau hit his head against the hard curtain and cut his eyelid open in one of the final scenes. Bleeding severely, he crawled backstage. Actors backstage rearranged their roles and replaced Andrei in all the remaining scenes. The audience didn’t notice anything. Of course, we rushed to help him, but later I felt so proud of our actors: Andrei solved the problem courageously, other actors reacted quickly, stayed calm and chose the right response to the emergency. In these moments, you see clearly they are a group of professionals, soulmates, people who love and appreciate each other and stay devoted to their work.

Liubou Kudzelka | How do you think the ideal transformation of a Fortinbras students looks like at the end of the course?

In the “ideal world”, it is a professional actor who fits BFT’s cast, who has played several bright roles, written a debut play, staged maybe not a show, but at least some fragments or scenes. In addition, he or she began to understand the global theatre context and can discuss relevant theatre phenomena or events. What is the most important is that it’s a person who is interesting to work with and talk to.

Can you recall examples when a Fortinbras student works successfully outside the laboratory but using the skills received in the studio?

Of course I know such people. The skills you receive here only help you and in no way hinder you from fulfilling your potential anywhere. However, there’s one problem with it. Belarus Free Theatre is a structure living in a very dynamic mode to fit today’s speed of art and society. If we speak about art, there are only a few similar institutions, both in Belarus and worldwide. Apart from that, Belarus Free Theatre is always in the spotlight of the world media. Any BFT’s successful experiment and any successful new work attract much attention, which helps us not lose pace and sometimes receive great information support.

When someone leaves us, to continue their career, they need to find a company that wouldn’t slow down their development rate, but on the contrary, would multiply any worthy efforts of articulating new creative ideas. It’s hard to do, especially if you live in Belarus, where the overwhelming majority of creative companies exist outside the global context.

Nadzeya Krapivina | Do you agree with the opinion that BFT’s works can be divided into two categories: performances “for tours” and those for “internal use”?

No, I strongly disagree with this opinion. The matter is that we have never divided our performances like that. We stage all our performances for the Belarusian audience, even if we create an English-language show. For example, the performance Trash Cuisine was translated into Belarusian after being staged in English. Now the more chamberlike variant is shown in Minsk underground.

There are performances that were staged in Minsk, and they were important for the Belarusian audience, but the international audience didn’t really understand the context. But it doesn’t mean we don’t propose them for festivals or touring venues around the world. For example, we included the performance A Flower for Pina Bausch, which was initially staged by Vladimir Shcherban in Minsk, in our tour set in Hong Kong, and it received rave reviews from the Chinese audience.

A scene from A Flower for Pina Bausch

Of course, we have the strategy, the theatre must grow and create not only small performances, but also large-scale shows. Concerning the latter, we have performances like Burning Doors or King Lear which we can’t play in Belarus. We can’t play them not because they were created for the international audience, but because no one will allow us to lease a big venue in Minsk to show them for political reasons. However, we regularly get round the problem by live streaming our shows from big venues around the world.

Aliaksandr Dukhan | About a year ago, you proposed the idea of using a VR suit in theatre. How close have you come to putting the idea of tactile theatre into practice?

A few variants of the VR suit are ready and undergo a testing process. As soon as we decide on the parameters we need and release a batch, we’ll be ready to begin working on the first show involving haptic suits. I hope we’ll be able to discuss it in details by the end of next year.

We were the first in the world to speak about tactile theatre. Of course, we want to be the first to bring this idea to life. But we won’t be upset too much if won’t be the first to do it, because we understand how this technology concept can be important for the development of theatre, I mean not only tactile theatre, but also augmented reality theatre and fully virtual theatre.

Many know about your passion for culinary art. Which cuisine is “the cuisine of your heart”?

If I had had this question two decades ago, I could have answered it quickly and unambiguously. For example, “Mediterranean”. But now I can’t give a simple answer. The more you like culinary art, the wider the range of your favourite cuisines, products and dishes. You begin to understand there are no bad products – everything can be prepared so that it can be tasty. If I had been told in my childhood that I would love beet, asparagus, cauliflower or broccoli, I wouldn’t have believed it. But today these products are very popular, and any Michelin-starred restaurant uses them on par with eels, marbled beef or urchins.

Unfortunately, there are not so many popular cuisines in the world – French, Italian, Greek, Spanish, Indian, Thai, Japanese and Chinese. About a dozen of cuisines, for example, Peruvian or Portuguese, claim popularity. But this is a miserable amount, considering the fact there are about 200 countries in the world and cuisines of most countries have their advantages, interesting nuances and beauty. I admire such people as René Redzepi, who literally created Danish cuisine with his team at Copenhagen's restaurant Noma, or Virgilio Martínez, who makes what seems impossible to promote Peruvian cuisine – brings it from the shadow to the light.

By the way, we plan to launch a culinary course as part of Fortinbras’s programme so that our students could understand that a recipe of an excellent dish and a recipe of an excellent performance are of the same nature.

Subscribe to our mailing list: