Vladimir Shcherban stages a new play after large-scale celebrations of the theatre's 10th anniversary. Read his new interview about the new work, plans for the future, post-festival thoughts and principles of his work.

About theatre series Ghosts' Territory

A couple of months ago I saw an ironic Map of Belarus' Famous Ghosts. I got interested. I came to the idea to carry out my own research to understand what is true and what is not and delve into collective unconscious. Quite an interesting process.

Actors had a task to find witnesses, make a contact with them, make a contact with a ghost, if possible, and spend a night where it is thought to live.

It became clear during the research that a handful of ghosts mentioned in that ironic map does not include all ghosts. We have more. Moreover, we found out that actors have their own ghosts.

The actors also worked as journalists. They made records. We had lots of information that naturally began to arrange itself into thematic blocks. Into episodes, let's say.

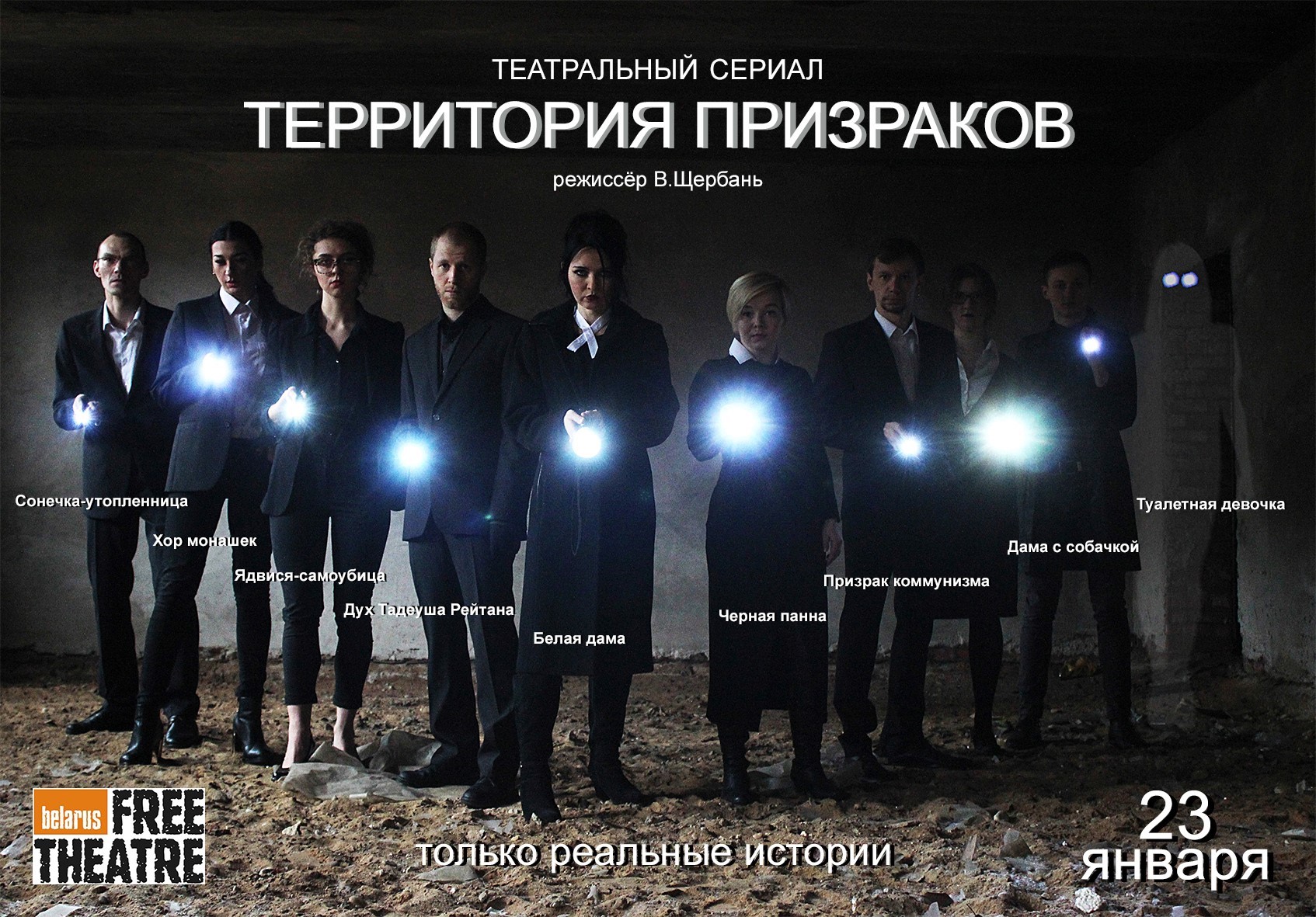

Performance poster

I think an actor must be able to do everything today. We had to study editing in its more cinematographic, not theatrical meaning. If an ordinary person can edit video with his or her iPhone, an actor should at least not to lag behind, but even be ahead.

It became interesting during the working process to make a portrait of another Belarus. It was interesting to go deeper in the countryside. Our usual themes are the capital and urban life. I am fascinated by rural dwellers, and I wanted to bring them to the fore. They are a vanishing world. They have a lively emotional memory mixed with fiction. I wanted villagers to tell these hipsters everything they remember and know. Of course, we contacted folklore specialists and ufologits, but we were more interested in free informal stories told in not so perfect language.

Of course, it is also ironic. This is a very “watchable” topic. People like to be thrilled, so television constantly refers to this theme.

Ghosts don't appear out of nowhere. This is society's request. Ghosts don't exist where they are not needed. They appear in real cultural and historical contexts. Any ghost can provoke debates, for example if it is Polish or Belarusian.

As a rule, people need a ghost that punishes. This is the picture drawn by ordinary people, not artists. They put their desperation into a particular image. They want to punish someone in this way, to restore justice.

We found the people that are absolutely informal for Belarusian theatre. They live far from Minsk and obey their special laws. While Minsk residents are struggling against real people, they are trying to deal with ghosts.

We don't say “premiere” now. We only touch on the topic. We are going to show the episodes and select the best pieces, and this will be the premiere.

About series

I didn't watch series at all until recently. I though it was an unworthy genre. World cinema is in a serious crisis now, so series became a space for experiments. This is a paradox. Today's series are not series with 500 episodes in each season. No, series are supposed to have six, nine episodes. They are in fact films that require much attention. You can't miss a single episode.

I can't say I like mystical series. Mysticism was the last thing that interested me in Ghosts' Territory. On the contrary, I was interested in reality. In particular real people.

The first series I watched from beginning to end was David Lynch's Twin Peaks. After that I watched Alan Ball's Six Feet Under. From the latest works – Fargo and Flesh and Bone. To understand the difference between British and American series, you can watch the original Queer as Folk by Russell T Davies. Russell T Davies has recently done another revolution by “playing” with the series structure and making the trilogy Cucumber,Tofu, and Banana.

Series are like five-act plays that no one stages today. It is an excellent opportunity for an actor to construct and develop the image.

Feelings after Staging a Revolution festival

Ghosts' Territory is the first play after the celebration of the theatre's tenth anniversary. I think it's not natural to make plans for next 10 years. Of course, I have to make plans in the UK, but you mustn't focus on it.

I'd like to stage a play only with British actors. I think it will be useful for our actors as well.

The ideal and luxury for a theatre is to do what you have right now. We've always had this system. We are not a locomotive that moves somewhere. Life gives us different surprises. For example, I've begun to read plays from our biennale. I've read 13 awful plays by now. But it' quite possible that I'll read an interesting one tomorrow.

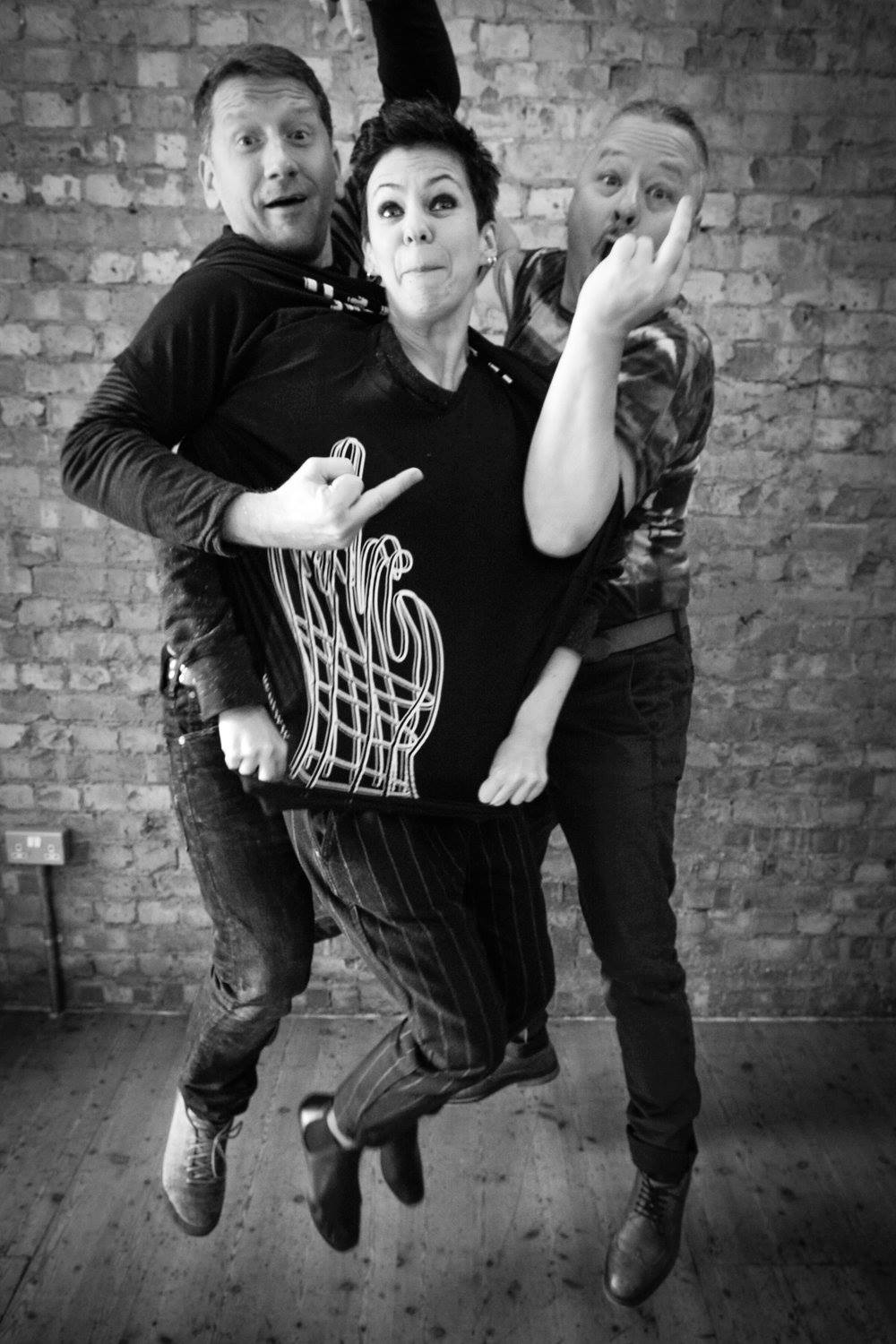

With Natalia Koliada and Nicolai Khalezin, photo by Georgie Weedon

Everything that happens updates us. After London and praising reviews, I wanted the actors to go to a village, see pigsties, meet people who don't know where London is and make contacts with them.

Restoring a performance is like rehearsing your own funeral. I think it would be useful for all of us to see how we were moving intuitively in the right direction.

This increased attention is like a heroin dose, I think. You are excited, you are on edge, but then you feel total devastation. The 10th anniversary is something you need to get used to. It makes you tired.

About principles of work

I heard when I was young that theatre was going to die. They still say it. Meantime theatre enters our life more actively. Theatre used to “play life”, but now it “plays with life”, capturing and developing non-theatrical fields. I've heard about rehearsals of a performance in space. In fact, all experiments in theatre for the last 20 years were experiments with space. But Jan Fabre experimented with time in his new performance Mount Olympus. It lasts 24 hours: actors play, sing, sleep on the stage, wake up and continue playing. This is not a theatre. This is a lifestyle for performers and the audience. When I first heard about the performance, it took me some time to forgive myself that it wasn't I who created it. It's so simple and so genius. Theatre is another means of communication with audience. We can record the reality directly. We see plays that include 500 photos. And this is a play. Everything is mixed up.

In Belarus Free Theatre complete newcomers work along with experienced actors. You can't make allowance for their first steps, because you are working over a performance. You have to do some things at a very high speed. But it's our job.

In theatre you work just for one thing – to create a performance. The longer you know people, the more difficult it is to keep business relations, but it is necessary, otherwise you'll ruin the whole thing. I saw creative teams dying because they began to “play family”, play comfortable coexistence. Actors sometimes must conflict with the audience in order not to become slaves of their love.

In a devised show an actor goes through several circles of hell. He needs to find his point of view in a performance, write a text, find a form. It requires serious work, at least because writing is not for everyone.

The most difficult task is to find the common creative denominator. People are different. Some, who already saw success, need other stimulants in order not to repeat. Some need a kick in the butt to get them toned. A rehearsal is not just sitting and talking. A rehearsal is when everyone is on emotional edge. In this case we see results.

My task as a director is to make an actor look as convincing as possible in a performance, so that the audience look at him or her openmouthed even if they don't understand details. Another important thing is that an actor must do something new for him or her.

During Price of Money rehearsal, photo by Georgie Weedon

The state of creativity at a rehearsal is not very comfortable. It's like Fellini said: “To start making a film is like to infect yourself voluntary.” You must be concentrated as much as possible. You must completely obey the process and subject your sexual life to it. Your reactions must be acute. You must solve many technical issues. And the main thing is that you must be ready to do tasks from easy and elementary ones, like learning a text by heart, to complicated ones, like finding interesting metaphors. You delve into the creative hell. But this process is voluntary.

When a performance is presented to public, I will defend my team to the end, even if something went wrong.

“Interesting” is when you set difficult tasks for yourself. Sometimes rehearsal processes can be very easy. It is rare, but they happen if you've gone through many things, you and actors speak the same language and understand the common movement. In this case work is easy and pleasant, but roads to it are difficult.

Some need to sit alone before a performance and concentrate. Some need to walk around and talk. It's individual. There are no common rules. Sometimes it's better for an actor to say “I simply can't do it right now” after a long struggle with the material and himself or herself. I respect them for being able to say so.

You feel like a complete idiot, and you have to answer elementary questions how it begins. Any experience can't save you. Creativity is a very uncomfortable thing. Tennessee Williams wrote plays and then either used stimulants or went to a mental hospital. But he wrote goods plays.

On the other hand, I can't say it's a sort of self-sacrifice. It's a job. It's easier than my sister's job, who takes care of critically ill people. You suffer a little, but then things start moving, and you can do nothing.

It's just a need. One either has it or not. It's an internal need to accelerate the sense. You live calmly. It seems you are an ordinary person – borscht, dormitory suburb, wine, fucking – it's not the worst variant. But one time you get tired of it and you want to try to find the sense of borscht and so on. The most terrible thing is when passion disappears. Everything loses its sense in this case. It's natural. Sometimes it disappears for a long time. The process reveals your weak points. You can't interest anyone if you repeat the same things.

A Skype conference with audience in Minsk, photo by Carolina Poliakova

I am very demanding of actors. I don't promise anything good at the start, I only can try to talk a person out of it. And I am very happy if everything goes right. This is happiness to come on the stage and tell people your stories. It's so rare for people on the stage. I am happy that such things happen. They are wonderful.

About Fortinbras students

I don't talk much to current students. I want them to get relaxed a little, go through the preparatory stage. I want those who are ready for further tests to remain. Many people are attracted by the outer shell, especially after the festival. They don't understand how much work it requires. You sometimes think: “That's the person I need,” but then something happens and he or she leaves.

I am happy we have a new generation. You can't move forward without it. In my opinion, it's the ideal structure: we have the theatre, the laboratory – a source of staff for us, the drama contest – a source of plays and ideas. You can take ideas from different sources.

About theatre community in Belarus

Everything is disintegrated in Belarus. In my view, it remains disintegrated today. Actors, playwrights, critics – they don't communicate. Minsk is small compared to London, but they don't talk to each other all the same. This is a matter of tendencies.

I think the absence of good criticism is a result of the disintegration of these theatrical segments. These are interconnected things. An actor or a director can't grow because he or she doesn't play or stage contemporary plays, a playwright doesn't write, thinking “Why should I? They won't stage it anyway”, and a critic writes the same things again and again.

I think Tanya Artsimovich works system-wide. She writes reviews, stages plays, carries out workshops. For me there's Tanya and the rest Belarusian critics, let's say so. These Belarusian critics can't do anything with Tanya. She always has an independent opinion. This is the freest person in the Belarusian theatre community I know. Though we have never met.

This is so strange. You can be a critic or an art expert, you can like Free Theatre or hate it, but how can it happen so that you haven't seen BFT's single performance just to have arguments to hate us? As I understand, they simply don't like their work.

About audience feedback

I like criticism. It's pleasant. Audience feedback is like a kiss after sex. I think audience opinions are very constructive. I always encourage spectators to write their reviews however complex their impressions may be.

Sometimes you get so deeply involved in work that you lose the ability to look at things from a distance. Criticism is very useful in this case. You read some reviews and think: “Holy shit! No Belarusian critic can write something like this!”

I don't like the notion “premiere” in relation to theatre. I think it adds unnecessary stress to the creative process. That's why I prefer to make performances before the eyes of the audience. Or together with the audience. It begins with a public read-through, then it naturally expands, the text is put aside, scenes and metaphors appear and you understand one day that the performance is ready and spectators had a wonderful opportunity to go through all stages together with actors. Audience feedback is very useful here.

Comments on the internet are a charming forced necessity.

About desires

I'd like to speak English fluently, but you need first to start thinking in English. There are people whom I understand well and who understand me well, but this technical bullshit is an obstacle. On the other hand, there are people who think they understand me well, and I don't have enough words to explain to them that it's not so. So, it's more about necessity than about desires. I thought yesterday if I could work in office every day. It seems to me I've got used to live as I want.

With New York '79's actors

Recorded by Vika Biran

Subscribe to our mailing list: