An ongoing conversation between Belarus Free Theatre’s associate director Vladimir Shcherban and Georgie Weedon.

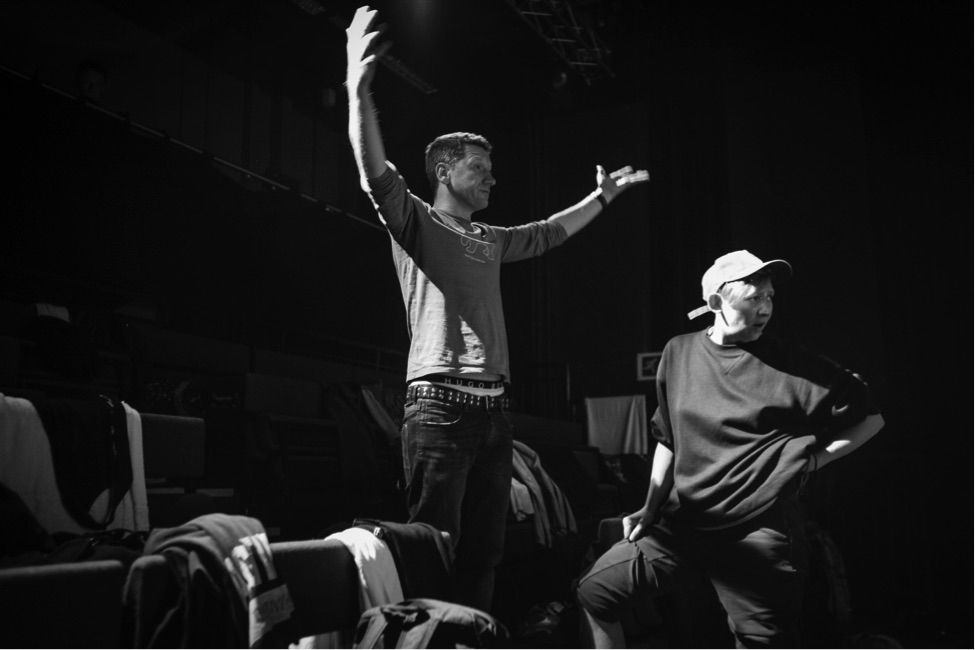

Photo: Director Vladimir Shcherban with interpreter Sasha Padziarei by Georgie Weedon

Described by Mark Ravenhill as an extraordinary talent, the multi-award-winning associate director of Belarus Free Theatre, Vladimir Shcherban, talks to Georgie Weedon in a series of conversations about his life in theatre, both in Belarus before he was exiled and now in London.

Conversation One: Beautiful moments in Minsk, the salvation of theatre, staring at rats, and wedgies.

Read here on BBC Arts: Exiled but not silenced

Conversation Two

GW: How did you come to help start the Belarus Free Theatre? What were you doing before?

VS: Belarus Free Theatre is not just a brand or a company for me, it is a very special place where very special people have met and who have shaped it into very special something, ten years ago. I worked at the Belarus National Theatre (it's the biggest achievement a young director could ever hope for in Belarus) and I was considered an expert in production of classical plays. Indeed I enjoyed it until the moment I realised that there was a huge gap between what I was doing and who I truly was.

What was happening with me and around me become much more interesting then the “actions” in classical plays. I faced the issue of self-identification, yet without one you cannot move forward either in life or in art. And in this exact moment I read some British plays – by Sarah Kane and Mark Ravenhill - they were revelations to me because they spoke the language of my thoughts.

First of all I produced “Some Explicit Polaroids” by Mark and even showed it once at the National Theatre in Belarus though it was followed by a tremendous scandal which went all the up to the Ministry of Culture. It was made clear that if I ever brought that kind of crap on stage again I would be fired. However I was already on my way so I produced “Psychosis 4.48” by Sarah Kane, they banned a showing of it at the National Theatre.

Together with two actresses who played in the performance we started to search for a place to present the play. Then I thought of Kolia and Natasha who had organized the “Free Theater” drama award a month before. After a long period of searching we had our first night of Psychosis in a small bar. Kolia and Natasha came to see the premier and we stayed together ever since. We lived from one performance to the next and that was how I gathered five actors in 2005 who then become the “golden” company of the theatre and whose contribution to development of the theatre is priceless.

I was fired from the National Theatre, I even sued them. A man who received my appeal to the court said: “We call such cases a pain in the ass. I assure you will lose because you are suing the state apparatus, but if you want to fell like Don Quixote who's fighting one's shadow – go for it”. He was right, I lost the case though I won much more – I won the freedom of art.

GW: Who has been most influential in your outlook on life and why?

VS: When I was ten I happened to get into a boarding school; there were children who never felt any parental care in their lives. Children abandoned by their families, by the society. Children who lived under strict rules since they were born. They taught me how to get around any regimes or rules. Sometimes in the evenings, after bedtime, we secretly came together and they asked me to describe how it felt living in a family, when you are needed. And I whispered them my stories. I was growing up with them, together we made good and not really good things, we cried songs together, together we fell into a mundane cruelty.

On graduation many of them started to take revenge on society which had denied them. It resulted that some of them were sentenced to execution by shooting, some killed themselves, some went on the bottle. Yet there is no doubt that without them I wouldn't be who I am today.

Photo: Shcherban directing by Georgie Weedon

GW: What question should I be asking you?

VS: Recently, I’m interested in finding an answer to the question what is the homeland. For most of citizens of Europe it's just the place where you were born, but for people from the post-soviet countries this question is still rather delicate. Society is strictly divided into those who stayed, and those who left. It brings out joint offences, blames and accusations. And here I am trying to understand what homeland is for me. I was born in Ukraine and lived in Donetsk for my first five years, then I spent twenty five years in Belarus, and now I've been living in the United Kingdom for five years. Where is my homeland and why don't I feel any homesickness to any of these places? I assume homeland is not a particular place strictly measured by a well-guarded boarder, but some sensitive feeling of the space connected to earth. My homeland is that wide tree in my aunt's yard in Donetsk, where I've spent lots of time when in my childhood eating tich mulberries right from the branches, soaking the juice of earth.

The war is there now so I am not sure the tree is still alive. And homeland for me means the taste of sun from those berries, just like the taste of the petite madeleine cake for Marcel Proust from which the masterpiece “Remembrance of Things Past” arised.

GW: You have a unique method of devising theatre with your ensemble, can you talk about the BFT devising process? How does a BFT play start, and come onto the stage?

VS: As a director I first of all shall not obstruct the birth of a performance. I see myself as a “professional audience”, I need to hear what the audience is silent about today in the most eloquent way. The first thing I tell the actors is not to be afraid of being silly, let's do what comes to our minds, lets search for the body's reaction to the chosen subject. I don't like to discuss the idea for too long. The main goal is to make our imaginations work. We share images, associations and we work out tons of unique material, and each rehearsal turns into a one of a kind performance which can last for up to ten hours every day. It lasts for five weeks. Then the process of selection and development of selected pieces starts. At that time I just ask myself as an audience, which performance I would like to watch today, what would truly excite me. The problem of many theatrical people is that they very quickly forget that they used to be in the audience that's why we see so many pretentious, boring and meaningless performances. Nevertheless, it is hard to say that we have any certain once-and-forever chosen method, as it conflicts with the idea of our theatre itself – which is to continuously work up new methods and techniques. Yet the goal remains the same – to talk to the audience about things they prefer to silence.

Photo: Shcherban directs Belarus Free Theatre’s Price of Money, playing as part of Belarus Free Theatre Staging a Revolution Festival 2nd -14th November 2015, streaming live every night on Ministry of Counterculture.